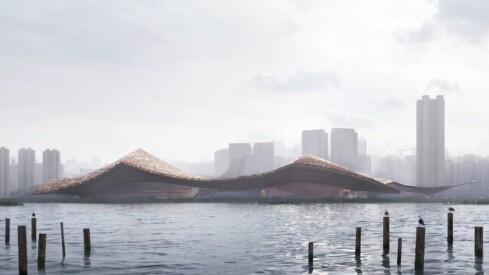

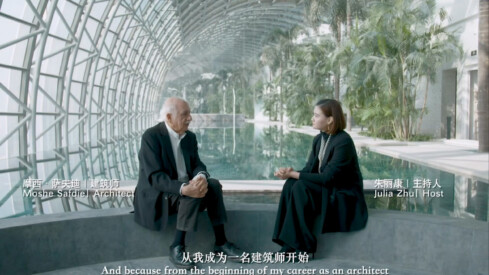

Shelter: The Streaming Platform Every Architecture Nerd Needs

Launched in the summer of 2020, Shelter is a self-described streaming platform for design nerds. Founded by Australian actor and producer Dustin Clare and his wife, Camille, the couple describes Shelter as being part of the next wave of streaming. Rather than casting a wide net focusing on general entertainment (e.g.,