ABOVE: Sharing The Story Behind The Architecture Of The Estonian National Museum

Since I have started writing for APAlmanac, discovering how other photographers and film-makers using are motion to create a narrative about architecture has been fascinating. Even the recent ZoomedIn Festival heavily touched on this subject matter as part of their talks. My limited experience of documenting residential architectural projects through motion has had its challenges, especially to craft something with purpose and intent — an effective storyline. I have had an inner battle on how to create a short film about a residential project that tells a story rather than a sequence of clips that merely moves through space.

Recently, I discovered a short film, Above, based on the Estonian National Museum by Indian Cinematographer, Vishal Vittal, from Bangalore (India). Initially, when I saw this short film, I was mesmerized by the sheer beauty in which it depicted an architectural project of such national importance, leaving me with more questions than answers.

I got an opportunity to speak with Vishal. His backstory is as fascinating as his film. He had an ambition of wanting to study abroad and left India to go to Prague to study cinematography at the Academy of Performing Arts in 2012. At the same institute, two of his favourite film-makers, Miloš Forman and Emir Kusturic, had studied there as well. Upon completion of his studies, he assisted and worked towards completing his first feature film in India. Later, in 2016 he decided to pursue a Masters in Cinematography through a program known as Kino Eyes in Europe.

As part of his Master’s course whilst in Estonia he was tasked with creating two films. One of the films was on the theme of architecture, for which Vishal had liaised with the Union of Estonian Architects who had shortlisted ten buildings, of which some were designed by Estonian architects. He recalls the moment, he arrived at the Estonian National Museum, he was in awe of the architecture and wanted his film to be centered around this specific symbol of Estonian national pride.

The design of the museum was chosen out of an international design competition and the winning submission was by an architectural collective known as DGT which comprised of three young international architects: Dan Dorell (Italian-Israeli), Lina Ghotmeh (French-Lebanese) and Tsuyoshi Tane (Japan).

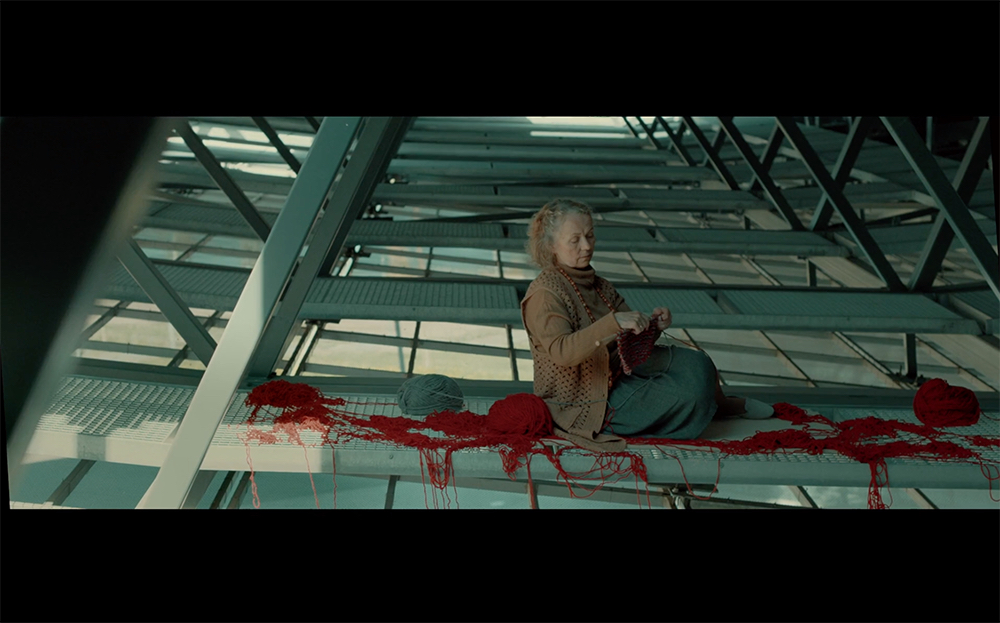

The museum had symbolized the nation’s struggles with occupation by foreign powers (Swedish, Russians and Germans) and their freedom in gaining independence in 1991 from Russia. This had formed a cornerstone of Vishal’s narrative of his short film’s first iteration focusing on the idea of freedom of expression. He explained that he had a vision of an Estonian man who treats the museum as his home, moves around and lives there which was in part inspired by the work of French filmmaker, Jacques Tati, whose films focused on the absurdity of life. The character becomes a piece of art that the visitors of the museum would look at it.

Vishal’s first iteration didn’t quite appeal to the Union of Estonian Architects so he had to revise his narrative and focused on the concept of freedom of expression. From his research into Estonian history during the Soviet occupation, he found that people were influenced by the fashion sense of the west which was oppressed by the Soviet regime. One of the more popular fashion items in that time were jeans pants, that would be smuggled out of Finland. Furthermore, people would be seen carrying around plastic bags with “coca-cola” written on it and some even used it has school bags. Additionally, people would use special antennas to catch Finnish TV signals as the Soviet would sensor what the Estonians could watch. These symbols of defiance against the Soviet regime were one of the ways Estonians fought for their freedom of expression and if caught the punishment was far worse.

These stories led to the notion of how fragile and intangible freedom was in the days of occupation and how quickly you would lose it if you got caught. In the film, Vishal used a soap bubble as a metaphor to express the intangible nature of freedom.

He further expanded on the notion of freedom in the scene where there is man on a bicycle who can be seen riding through the museum but as the scene unfolds you see he is fixed – the illusion of freedom Vishal had portrayed and partly inspired by the film, Stalker, directed by Aleksandr Kaidanovsky. The regime gives people a sense of freedom but in fact are tied bound by rules and oppressed.

The film itself is void of any atypical architectural elevations because Vishal wanted to avoid the cliched interpretation of the museum. Instead, he chose very specific vignettes that would allow him to use the architectural elements of the space to frame the characters within. He indicated that he had not storyboarded the entire film instead based the scenes on key perspectives he had seen on his multiple visits to the museum.

When asked about difficulties during the two-day shoot, Vishal admitted that the hardest aspect was the bubble itself. As much research he had done online determining the best way to produce bubbles, his team were unsuccessful. Fortunately, his producer found a duo in town who volunteered on the second and final day of the shoot to create the bubbles. This impacted Vishal’s original vision of film because the bubbles were supposed to be in the same frame as the characters and as a compromise it ended up in their own frames.

One of the crucial elements that are often overlooked in films is how the sound design designed for the film. Vishal’s sound designer wanted to include a large musical component but himself and his editor went in the opposite direction. Keeping the sound design purposefully minimal with music as the intent was to further engage the viewer with the architecture itself. For example, the attention one pays to when the bubble appears in the scene is through how the sound is engineered to follow the bubble as it drifts through the frame. When the attention needs to shift from the bubble to people, this is all done through sound.

This short film demonstrates that the story of architecture can be told from many tangents however, the most emotive perspective would be of the people the architecture is about. Furthermore, filming gives architecture a different depth in how it is represented and more specifically, bringing out the experiential qualities of the space to the viewer.

p.s If you have an interest or are curious about the world of film-making then I would highly recommend tuning into the podcast of Roger Deakin titled Team Deakins.