Extraordinary Black Architects To Learn About

From the stairs that Rocky Balboa ran in his training montage, to homes of Hollywood celebrities, to some of the most iconic public projects in the world, Black and African American architects have designed many of the architectural icons and integral buildings that we see and use every day.

Household names in architecture tend to be Frank Lloyd Wright, Gehry, and Le Corbusier, but there are lesser-known architects with incredible stories of rising through the midst of adversity and their experiences are important to know. While this list is by no means exhaustive, may it whet your appetite for learning the background of both past and present Black architects whose careers should be known, celebrated, and reflected on.

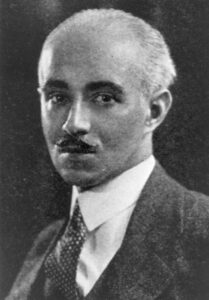

Paul Revere Williams (1894-1980)

Paul R. Williams was truly a spectacular man and a spectacular architect. Born in 1894, he was orphaned as a child and grew up in a foster home. Fortunately, his foster mom was adamant about pushing his education and artistic talent. Living in Los Angeles in the early 1900s, he grew up in a time when “the California dream attracted people from across the United States, and they mixed together with little prejudice,” but that’s not to say that Williams didn’t experience adversity based on the color of his skin. In high school, a teacher tried to discourage Paul from pursuing architecture due to the perceived difficulty of attracting affluent White clients, and by expressing that Black clients wouldn’t be enough to sustain his practice.

Paul’s love for architecture was not snuffed out by his teacher’s put-down. He worked his way through major Los Angeles design firms, honing both his architectural and business skills. Paul became a certified builder in 1915 and officially a licensed architect in the state of California in 1921. He opened his own practice and went on to become the first African American member of the esteemed American Institute of Architecture (AIA) in 1923.

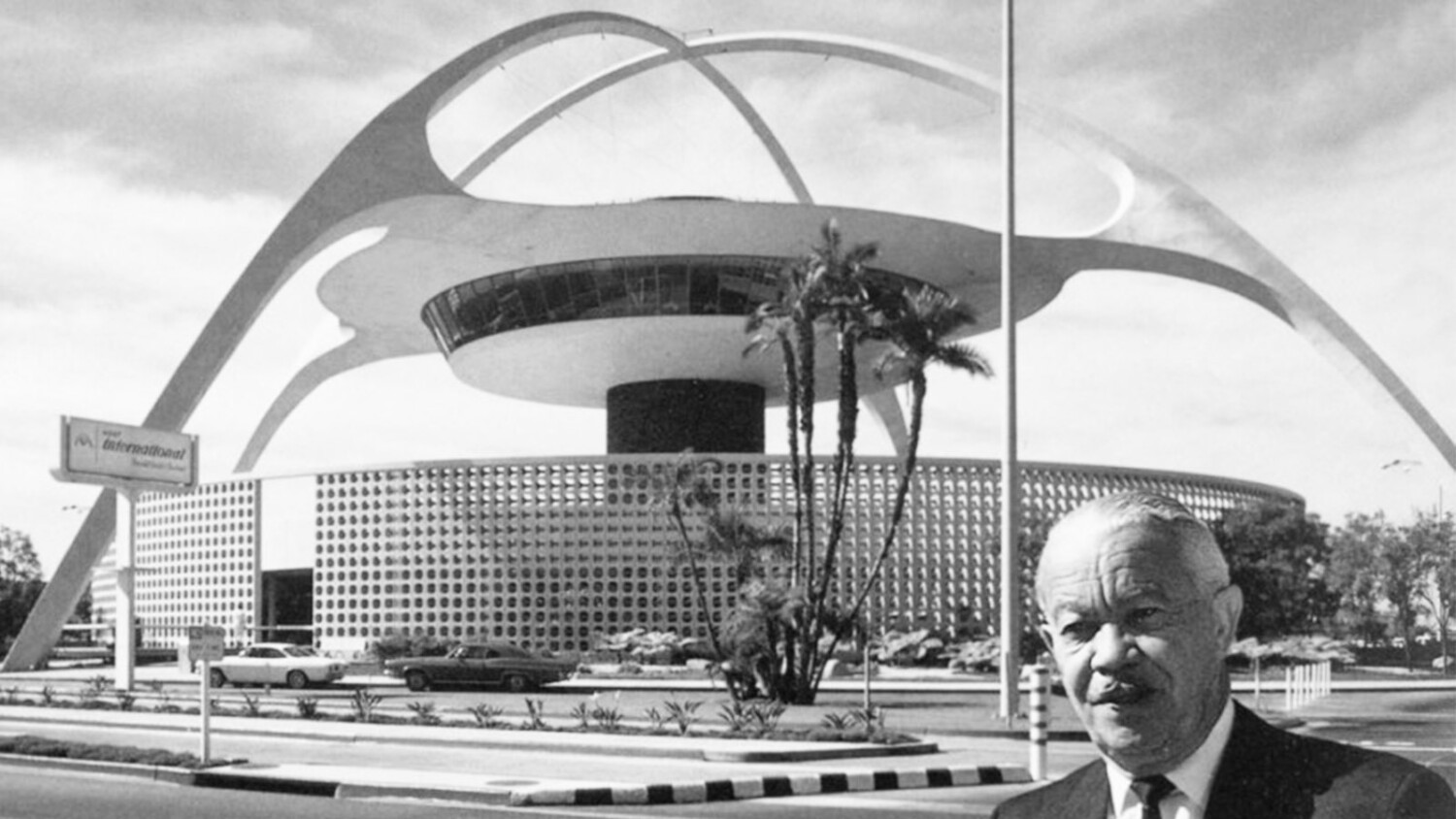

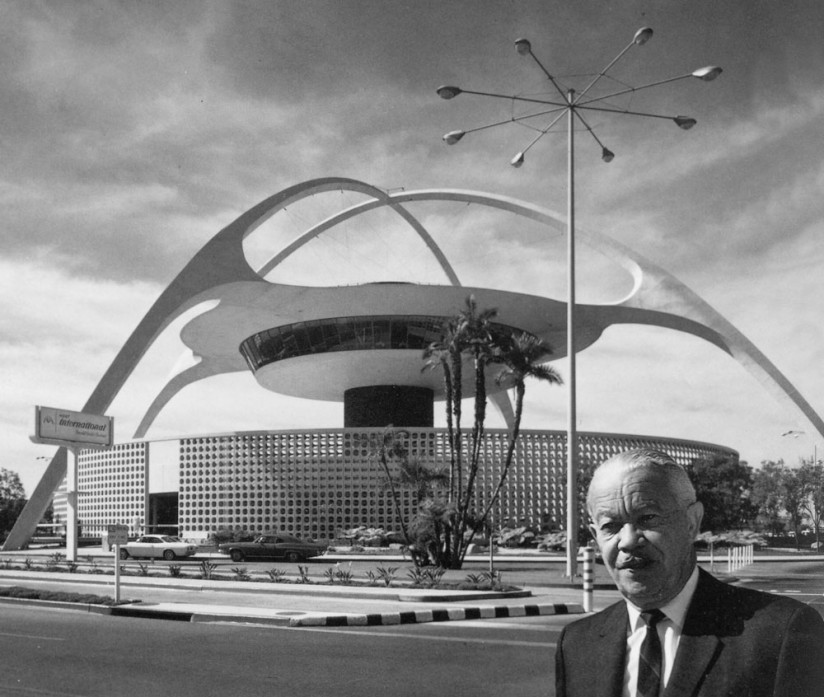

Paul kicked off his career by building both affordable housing and large historic revival homes for rich clients, discrediting his old teacher’s remarks. As his reputation grew, he began designing what are now historic icons of architecture, like large scale works including Saks Fifth Avenue, the Palm Springs Tennis Club, La Concha Motel, LAX Theme Building, and the Mutual Life Insurance Building. Paul created outstanding homes for Hollywood’s stars like Lucille Ball, Frank Sinatra, and Bert Lehr. Paul’s career picked up an enormous amount of steam as he became not only a nationally recognized architect, but one with a global reach, designing residential, commercial, institutional, and public spaces.

Paul R. Williams as photographed by Julius Shulman

LAX Theme Building as photographed by Darren Bradley

Despite his exceptional talent and a virtually endless list of commissions, Paul Williams experienced the pains of a racist society. Paul had the unusual ability to draw sketches upside down. He developed this talent because, as a Black man, many clients were uncomfortable sitting next to him, so he drew their renderings from across his desk.

Not only was Paul Williams an exceptional architect, but an exceptional human being. He was a founder on the board of Broadway Federal Bank which supported the African American community that couldn’t bank or take out loans from traditional American banks. Paul often donated his time and expertise to projects he believed advanced the welfare of young people, African Americans in Southern California, and greater society. Paul was posthumously awarded the AIA Gold Medal — their highest honor.

“Our profession desperately needs more architects like Paul Williams,” said architect William J. Bates, in support of his AIA Gold Metal nomination. “His pioneering career has encouraged others to cross a chasm of historic biases…his recognition demonstrates a significant shift in the equity for the profession and the institute.”

Norma Merrick Sklarek (1926-2012)

Norma Merrick Sklarek was a tour-de-force of design, and an inspiring woman. Born in 1926 to parents who immigrated from Trinidad, Norma had an unrivaled talent for math and fine arts during her schooling. Her father — a doctor — saw this skillset and encouraged her to become an architect. Norma spent one year at Barnard college and then transferred in to Columbia’s school of architecture. She was one of two women, and the only Black member of her class.

“By her account, architecture school was difficult; many of her classmates were veterans of World War II, some had bachelor’s or master’s degrees, and they collaborated on assignments, whereas she commuted to school and struggled to finish her work on the subway or at home alone. As she said later, ‘The competition was keen. But I had a stick-to-it attitude and never gave up'” – from an article about Norma Sklarek on the segment Pioneering Woman of American Architecture by Beverly Willis Architecture Foundation.

After graduation, Norma applied to, and was rejected by, 19 architectural firms, not only because she was a woman, but because of the color of her skin. Discouraged, she became a draftsperson at the City of New York Department of Public Works, but felt her talent was being wasted and decided to sit for the architectural licensing exam anyway. She passed on her first try.

Norma Merrick Sklarek became the first licensed Black woman in New York in 1954. The magic started to happen in 1955 when Sklarek was offered a position at Skidmore Owings & Merrill despite a bad letter of reference from her Department of Works supervisor who was unhappy about her licensing achievement as a Black woman. At SOM, she was given large scale meaningful projects. In the evenings, she taught architecture at New York City Community College while being a single mother of two.

In 1958 Norma became the first Black woman member of AIA. In 1960 she moved out to Los Angeles and worked for Gruen.

The Pioneering Woman article goes on to recount “At Gruen, she was aware of extra scrutiny from her supervisor, as she was the only Black woman in the firm. As a new employee without a car, she took rides to work with a White male colleague who was consistently late. ‘It took only one week before the boss came and spoke to me about being late. Yet he had not noticed that the young man had been late for two years. My solution was to buy a car since I, the highly visible employee, had to be punctual.'” Two years later she became the first Black woman licensed architect in California. She rose to become Gruen’s Director of Architecture. Later she took the position of Vice President at Welton Becket Associates, and in 1985 became the first person of color to co-own an architectural practice, Siegel Sklarek Diamond.

Norma Merrick Sklarek worked on monumental projects like Sand Bernardino City Hall, the US Embassy in Tokyo, and Mall of America. In addition to receiving an AIA award, she lectured at Columbia as well as Howard University, where there is a scholarship in her name. Norma said “In architecture, I had absolutely no role model. I’m happy today to be a role model for others that follow.”

Julian Abele (1881-1950)

Julian Abele was born in 1881 to a prominent family in Philadelphia and throughout his life worked in many artistic mediums, from watercolor to furniture construction. Julian was always great at math and became the first Black student admitted to the Department of Architecture at the Ivy League school University of Pennsylvania.

His classmates nicknamed him “Willing and Able” and he won multiple awards for his design of a Beaux Arts pedestrian gateway, a post office, and a botany museum. He was the president-elect of the UPENN Architectural Society and the first University of Pennsylvania architectural department graduate of color.

Julian was sponsored by Horace Trumbauer and was given the opportunity to travel through much of Europe. He spent a hefty amount of time living and studying in Italy and France, which inspired much of his work. In 1942, Julian joined the American Institute of Architects. He was known for his gorgeous sketches and grand elaborate designs.

Julian Abele’s most noteworthy architecture projects are genuinely incredible; examples include being the primary designer of much of Duke University and his lauded design of the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He carefully drafted his signature style on the grand steps leading up to the museum which are the iconic All-American “Rocky Stairs” that people come from all over the country to run up and down.

Beverly Loraine Greene (1915-1957)

Beverly Loraine Greene was born in 1915 and was the first African American woman licensed as an architect in the United States of America. Her career developed side by side with the civil rights movement.

She attended the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign which was racially integrated at the time, where she earned her bachelor’s degree in 1936. A year later, she got her masters in city planning and housing. Beverly was officially registered as an architect in Illinois in 1942, and worked at the Chicago Housing Authority as well as the first architectural office led by an African American in Chicago.

Greene was met by much adversity and found that in Chicago, the media generally ignored Black architects and their projects, making it even more difficult to establish herself in the industry. In an article about Beverly on The Architect Marketing Institue, doctoral candidate Nicholas Watkins shares “I’m not African American, so I didn’t go in with a preconceived feeling. It took going down to the University Archives and seeing images of Beverly amidst a sea of white male faces to appreciate the history. I had the feeling that segregation and racism were more of a quiet thing – subversive in their quietness…cancerous.”

Hoping to find greater opportunities in the field, she moved to New York City and took a job at MetLife. Beverly worked on the residences at Peter Cooper Village – Stuyvesant Town, which ironically she was barred from living in because she was Black. The Stuyvesant Town residences displaced an absurd amount of People of Color to be built, then advertised themselves as an “equal opportunity community.”

Beverly left MetLife soon after arriving and attended Columbia where she received a master’s degree in architecture. She began working with famed architects Edward Durrell Stone, Isadore Rosenfield, and Marcel Breuer. She designed the theatre at the University of Arkansas, the Sarah Lawrence College Arts Complex, the buildings at the University Heights campus of NYU, and most famously, the UNESCO United Nations headquarters in Paris.

Vertner Woodson Tandy (1885-1949)

Vertner Tandy was the son of a respected mason, born in 1885 in Lexington. During his formative years, he helped his father work in trades, and this fueled his interest in craftsmanship and architecture. Vertner attended Tuskegee Institute in 1904 and was the star student of the architectural studies program. Tandy transferred out the next year to attend the Ivy League Cornell University. There, he helped form the Alpha Phi Alpha, which was the first African American Greek letter fraternity.

Vertner was the first African American architect registered in New York, and his practice’s office was on Broadway.

Tandy was revered for his designs of New York Icons like St. Philips Episcopal Church, and Madam C.J. Walker’s (An incredible African American woman who was the first female self-made millionaire) mansion Villa Lewaro during the Harlem Renaissance. Vertner Tandy was the architect behind the Ivey Delph apartments which are now on the National Register of Historic Places!

Robert R. Taylor (1868-1942)

Robert R. Taylor was a deeply interesting man. In his life, he became the first accredited African American architect, and was second in command of the Tuskegee Institute, working closely with Booker T. Washington.

Robert was born in 1868, and his father was a prominent contractor/builder, grocery store owner, member of the Masonic Lodge, and a man active in city affairs. Robert worked closely with his spectacularly inspiring dad at his building company where they both agreed that he needed to formalize his architectural training, so he applied to MIT.

Taylor was one of just a few Southerners at MIT, where he experienced prejudice for being both African American AND from the South. He was a rockstar in class and scored well above the class average in all of his courses, not letting his peers shut him down. Writing a thesis on the thoughtful design of a hospital for soldiers, he captured the attention of Booker T. Washington and was invited to Tuskegee Institute to construct new buildings and teach architecture.

Robert Taylor designed much of the Tuskegee Institue’s campus, from The Oaks which was the president’s house, to Huntington Hall, Rockefeller Hall, and The Lincoln Gates. The Chapel which he designed, inspired the novel Invisible Man by Ralph Ellison.

Hopping back to Cleavland for a while to work on various other projects, Robert helped design the Alta Settlement House which served Italian Immigrants and was funded by the Rockefellers. He is the man behind Carnegie Library at Wiley College, the Masonic Lodge in Birmingham, Dinkins Memorial at Selma University, and endless other buildings throughout North Carolina, South Carolina, Arkansas, Michigan, Virginia, Tennesee, Texas, and Alabama.

Robert Taylor leaves behind a beautiful legacy. His great, great-granddaughter Valerie Jarrett was Senior Advisor to President Obama. There is even a postage stamp in circulation with Robert Taylor’s likeness on it.

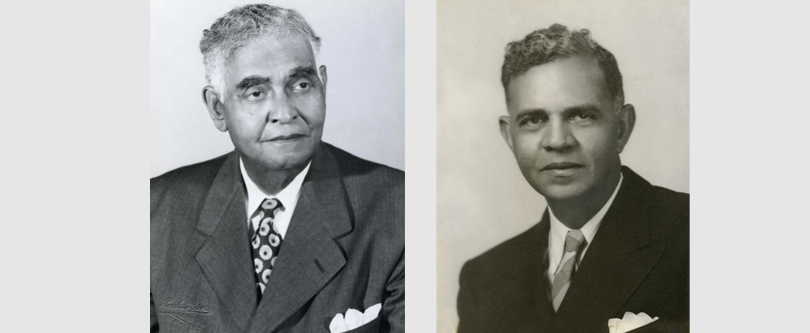

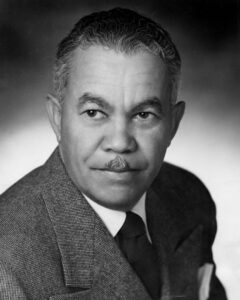

McKissack & McKissack (Past and Present)

McKissack and McKissack is a unique and astonishing architectural firm with a deep history, and is still booming today. It was the first, and continues to be the oldest, African American owned architectural firm in the United States.

McKissack & McKissack was founded by brothers Moses McKissack III and Calvin McKissack. Their father was a builder, and his father was a builder, specializing in brickwork as a slave. Moses apprenticed under a builder making designs, drawings, and doing the physical construction work of buildings in Tennesee. Calvin attended Fisk University in Nashville. The brothers started building residential homes and then were commissioned to build a house for the Dean of architecture studies at Vanderbilt University. They built the Carnegie Library at Fisk University, and various other scholastic and residential projects. The McKissack brothers’ practice began to pick up notoriety and expand outside of Tennesee.

In an interview with the New York Times, Cheryl McKissack Daniels — Moses’ granddaughter and the current CEO of the New York based McKissack firm — stated “Both Calvin and Moses McKissack went to architect school through correspondence and took their exam. First the board would not allow two black men to even sit for the exam, so they lobbied each board member until they found one that found favor with them. He said, “We know they’re going to fail, so let’s just let them take it.” So they took it and passed with flying colors. Then they didn’t want to give them the license. Eventually they did, because the national news got hold of these two black architects who passed this exam and were trying to get licenses, and the board members all of a sudden had this national notoriety and so they said we have to give them the license. Not only that, they helped them get licenses in 22 other states.”

A 5.7 million dollar grant from the federal government was awarded to McKissack & McKissack, which was the greatest sum ever distributed to an African American company by a federal contract. Moses was appointed to President FDR’s confrence on housing problems, and was awarded the Spaulding Medal. Later, Moses’ son William took over as president of the firm. After retiring due to illness, his wife Leatrice became the CEO. Under her leadership, the firm completed major projects including the 50 million dollar renovation of Howard University, and the construction of the National Civil Rights Museum.

Today McKissack & McKissack’s legacy is still thriving under the care of Leatrice and William’s twin daughters Cheryl and Deryl.

Cheryl has overseen the building of incredible projects such as JFK Airport’s Terminal One, Pacific Park, the modernization of Harlem Hospital, Lincoln Financial Field, and consulted on The Oculus.

Cheryl’s twin sister Deryl McKissack is the President and CEO of her own McKissack & McKissack in DC. Both sisters and their firms are experiencing great growth. Over the past 25 years in DC, Deryl has managed enormous and historic projects including assisting in the construction management of the Museum of African-American History and Culture on the National Mall, MGM National Harbor Casino, Navy Pier Centennial Projects in Chicago as well as the Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial in Washington, DC.

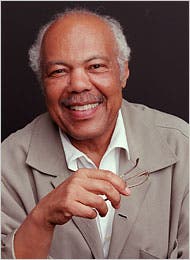

J. Max Bond Jr. (1935-2005)

J. Max Bond Jr. is one of the nation’s more prominent African American architects. Born in Kentucky in 1935, he attended Harvard University. He was one of 11 Black students to be targeted by a cross burning attack outside of his dorm there. Much like Paul R. Williams, Bond’s teachers tried to discourage him from pursuing architecture because of his race, although he carried on anyhow.

Bond kicked off his career working with French Modernist architect André Wogenscky, and later with Gruzen & Partners as well as Pedersen & Tilney. He lived in Ghana from 1964-1967 where he used exceptional design techniques on buildings like Bolgatanga Regional Library, eliminating the need for air conditioning.

J.Max Bond Jr. has worked in on countless high profile projects, such as the design of the museum section of the National September 11 Memorial and Museum, Audubon Biomedical Science and Technology Park, The Martin Luther King Jr. Center for Nonviolent Social Change in Atlanta.

He was the chairman of the architecture division of Columbia University, the Dean of the City College of New York’s School of Architecture and Environmental Studies, and was a member of the New York City Planning Commission.

Sir David Adjaye (Present)

Sir David Adjaye is a modern day Black architect who designs exceptional works all across the globe. David was born in 1966 in Tanzania, and was schooled at the Royal College of Art in London, as well as South Bank University. David founded his firm Adjaye Associates in 2000. The firm has studios in London, New York, and Accra. He has won the RIBA Presidents Medals Students Award.

David’s work is described: “While Adjaye has never adhered to a discrete style, his projects coalesce around certain ideas. Often set in cities struggling with diversity and difference, his public buildings provide spaces that foster links among people and explore how neighborhoods evolve, how new communities are created, and how unexpected junctures weave diverse urban identities and experiences into the tapestry of multiculturalism. Rethinking conventions, his designs speak to the specific time and place in which they were made.”

His work is a beautiful experimentation of light, color, and texture, which can be seen in some of his most renowned projects such as the Smithsonian Institution’s National Museum of African American History and Culture on the National Mall (which he designed with Phil Freelon and J. Max Bond Jr). The museum’s design is so unique and celebrated that Steph Curry released a shoe inspired by the architecture of the building. Adjaye is also known for great works such as the Moscow School of Management, the Museum of Contemporary Art Denver, and the Sydney Plaza Canopy designed with Aboriginal Artist Daniel Boyd.

Adjaye is a modern day master of architecture.

Saundra Little (Present)

Saundra Little is a highly esteemed architect and principal at Quinn Evans Architects. She earned her master’s in architecture from Lawrence Technological University in 1998. The emphasis of her career is on revitalizing urban neighborhoods and is held in high regard for “successful cultural, institutional, educational, and commercial projects of all sizes. Her work in design, revitalization, and adaptive use projects consistently demonstrates a respect and sensitivity to the unique architectural heritage of local neighborhoods.” Saundra is a member of the AIA, as well as the National Organization of Minority Architects, and is the founding member of the Advisory Board of Design Core Detroit.

Saundra works with writer Matthew Piper on “Noir Design Parti” which is a very influential organization, exploring Black architects and their effect on the development of Detroit. NDP uses tours, social media, books, and educational platforms to increase awareness and encourage People of Color to looking into architecture as a career choice! You can read more about Saundra, Noir Design Parti, and African American architects on Curbed Detroit.

It’s hard to deny that architecture has an effect on society, even if just subconsciously. The way people interact with the built environment and how it makes them feel is important. Black and African Americans are vastly underrepresented in architecture, making up just 2% of the licensed architect workforce. In an effort to bring more awareness to this field, schools like University of Texas at Austin and Hampton University are working hard to visit elementary and high schools, exposing Black students to architecture and its viability as a career. You can read more about the effort to increase diversity at architecture schools here.