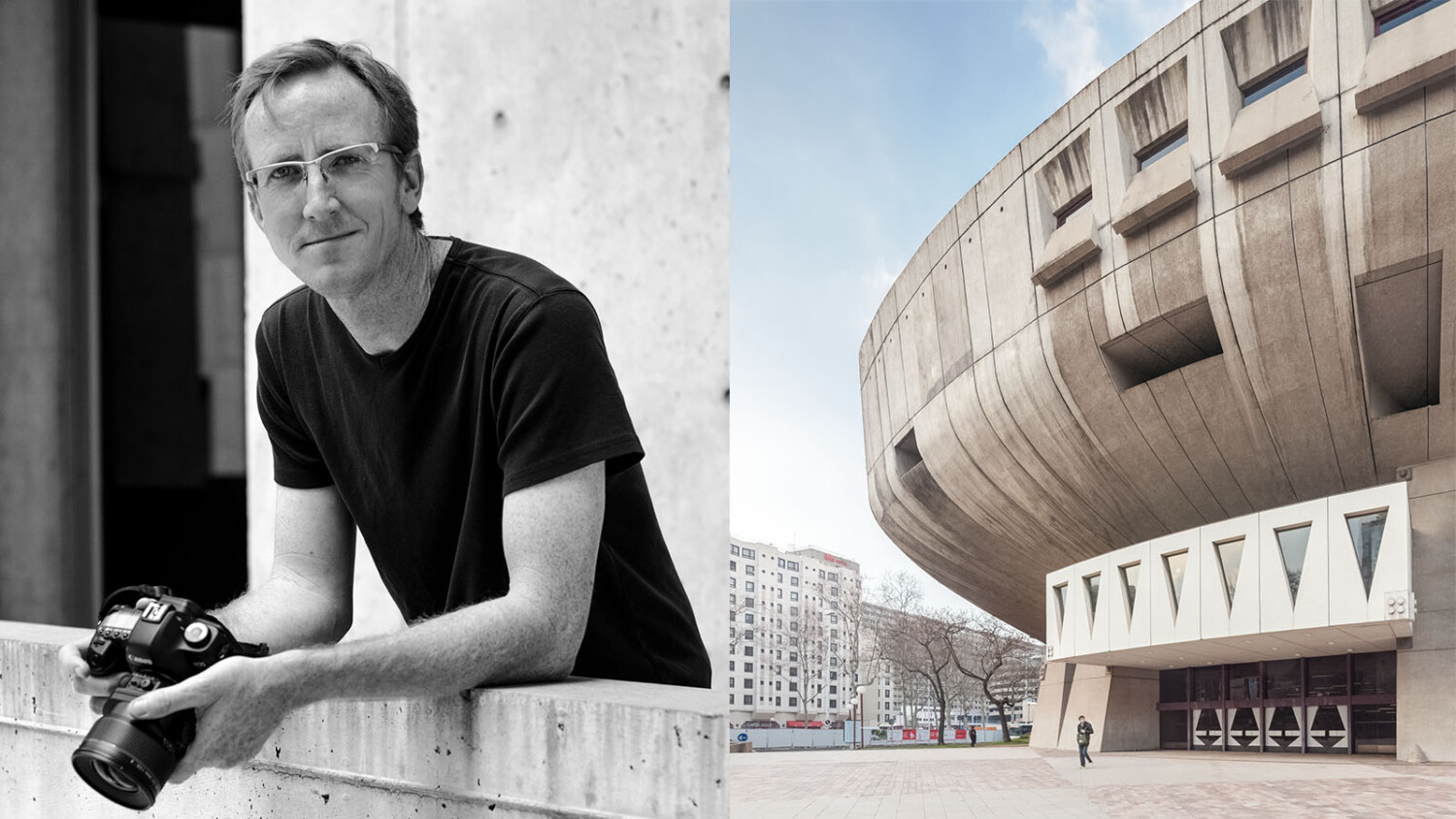

Interview: Darren Bradley, The Global Mid-Century Modern Specialist

Darren Bradley: TED talker, Dwell cover boy, global traveller and book author. Not bad for an architectural photographer! I met Darren a few years ago at an AIA award ceremony and instantly found him fascinating; so I couldn’t be happier to make this interview happen. Darren has dodged alligators, run from security guards, and slept in Florida’s sketchiest hotels in his quest to be one of the world’s preeminent Mid Century Modern specialists.

Mike: Thanks for taking the time to be interviewed by APAlmanac. To get the ball rolling, can you tell us how you got started on the path of architectural/interior photographer? Were you fascinated with architecture before picking up a camera, or did picking up a camera teach you about architecture?

Darren: Thank you for the opportunity! I’m definitely more interested in architecture than photography. I’ve always been interested in buildings and architecture, and wanted to be an architect as a kid. But I was discouraged from that because I’m terrible at math. It was only much later that I realized that many architects are, in fact, terrible at math! Architectural photography has been a way for me to re-connect with my first love of architecture.

I actually did study photography in high school; I set up a darkroom in my parents’ laundry room, and was the photographer on my school newspaper. I even worked in a darkroom while at university for a while. But I was pretty burned out on photography as a result, and there was a period of about 7 years where I didn’t even touch a camera. I moved to France in 1994 and I didn’t even bring a camera with me, it was that bad… I have almost no photos from that period of my life.

When I returned from France in the summer of 1998, I picked up a little digital point & shoot camera and started photographing the mid-century modern buildings around town that I liked – many of which were unfortunately getting demolished or modified beyond recognition. That was the first time I’d used a camera in years, and those photos were admittedly terrible – honestly, I had no idea what I was doing. Like most photographers, my photography training hadn’t really been focused on architecture, so I was also frustrated by how poorly my photos reflected what I saw and liked in these buildings.

As a result, I resolved to learn architectural photography. Gear was upgraded, and down the rabbit hole I went. Over the years as my photos got better, I gradually began getting contacted by books and magazines asking to publish them (editor note: Darren’s instagram account, @modarchitecture, grew by leaps and bounds over this period as one of the only accounts featuring these super interesting projects) Once I started getting published, I started getting commissions from architects and developers to photograph their new work… and here I am today.

You’re one of the most well-traveled architectural photographers in the world; what’s the craziest architectural photography related story you have from one of your projects? There’s gotta be some wild ones.

Oh man, there are lots; as you know, architectural photography is different from most other types of photography because we have to go to where the buildings are; that means there are always a lot of variables like weather, construction, delivery vans, over-zealous security guards, man-eating plants, and other things that are completely beyond our control. So you constantly have to roll with the punches and improvise.

A couple of years ago, I was shooting a former IBM building in Boca Raton, Florida. I had arrived late the night before and had forgotten to book a hotel in advance so I just went online and booked something that looked clean and cheap. There was a tropical storm, and it was raining bucket so I just wanted to get some sleep. When I arrived, there were all sorts of shady people hanging out in the hotel parking lot, and the front desk clerk had to buzz me into the office while sitting behind bullet-proof glass. As a general rule, I try to always avoid staying in hotels where the staff has to hide behind bullet-proof glass… But it was late and I was tired, and raining, so I did it anyway (famous last words).

Queue a night of no sleep. Prostitutes and crackheads kept knocking on my door (I didn’t answer), and were making all kinds of noises outside: yelling, banging, who knows what else… (editor: what kind of banging?), and in the adjoining rooms, more of the same. I tried ringing the front desk, but they had disappeared. At one point, I heard cops outside, and thought that would be the end of it. But the cops soon left and things started right up again.

I got up before dawn after a restless night. The skies were clear and there was no sign of the shady people…. I had slept in my clothes so was able to make a quick exit. I headed straight to the building I was there to photograph, a few miles away. It was still dark when I got there and not very well lit at the site. I was all alone – not another soul around – as I walked around in total darkness through this beautiful mid-century campus (the former IBM complex at Boca Raton is a large complex of Brutalist buildings designed by Marcel Breuer situated in a park-like setting, wrapped around a large pond with grass and trees throughout). At 5am, it was all just shadows and quiet as I tried to feel my way around the unlit site. I noticed some large fallen tree branches scattered around the site on the grass around the pond, which I attributed to the tropical storm from the night before. I just stepped around them and kept exploring, oblivious to anything but the architecture in front of me.

As dawn broke and I started to see better, I noticed that those weren’t logs around the pond… They were alligators! Fortunately, they were still asleep, but I nearly tripped over them and almost backed into one. So yeah, I can put a check next to “nearly eaten by an alligator” on my bucket list.

Hah, that’s unbelievable. But your work with Mid-Century modern buildings like the IBM campus has cemented you as probably the most accomplished Mid Century Modern specialist (barring Shulman, maybe?) that I know of. How did you fall into this specialized niche?

Thank you! Well, as I mentioned above, it was really my love of Mid-Century Modern architecture that brought me back into photography in the first place. Growing up in Honolulu and San Diego as a kid, everything around me was Mid-Century Modern. I liked it but didn’t really start to get obsessed with it until I saw it all start to disappear in the 90s. Also, I do have a history degree, and probably some obsessive tendencies, so when I get interested in something, I generally tend to go all in. So now I not only photograph these buildings, but I also lecture on the architectural history of the period at various universities and conferences around the globe. It just sort of snowballed, I guess.

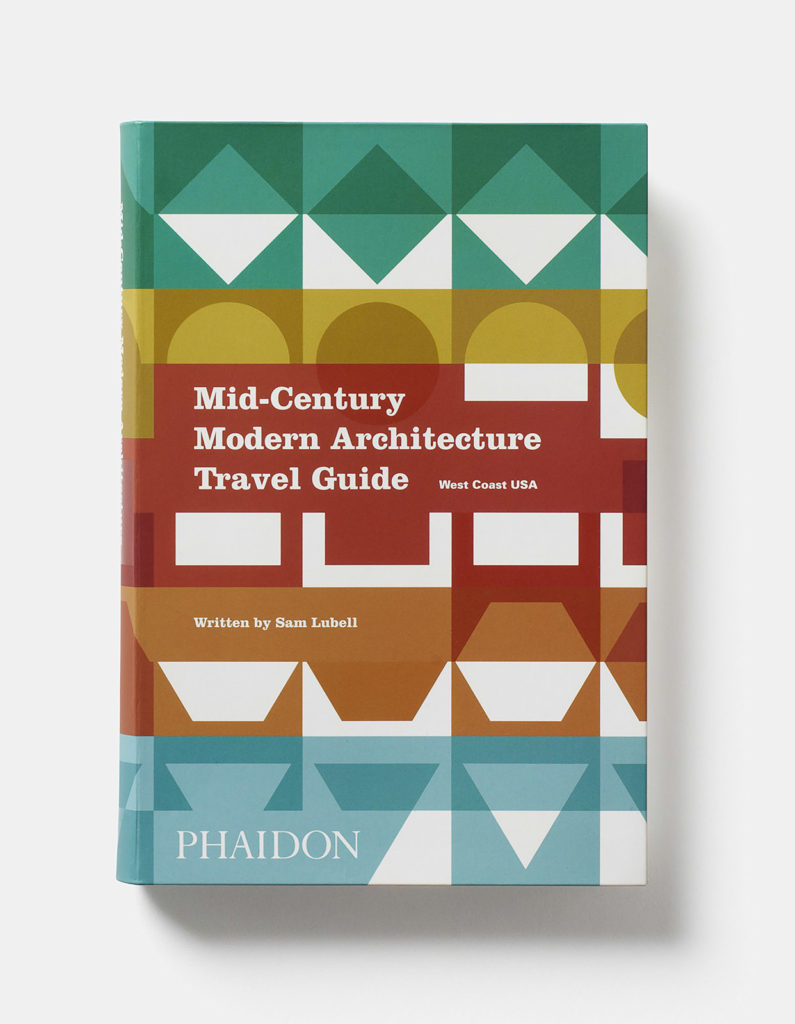

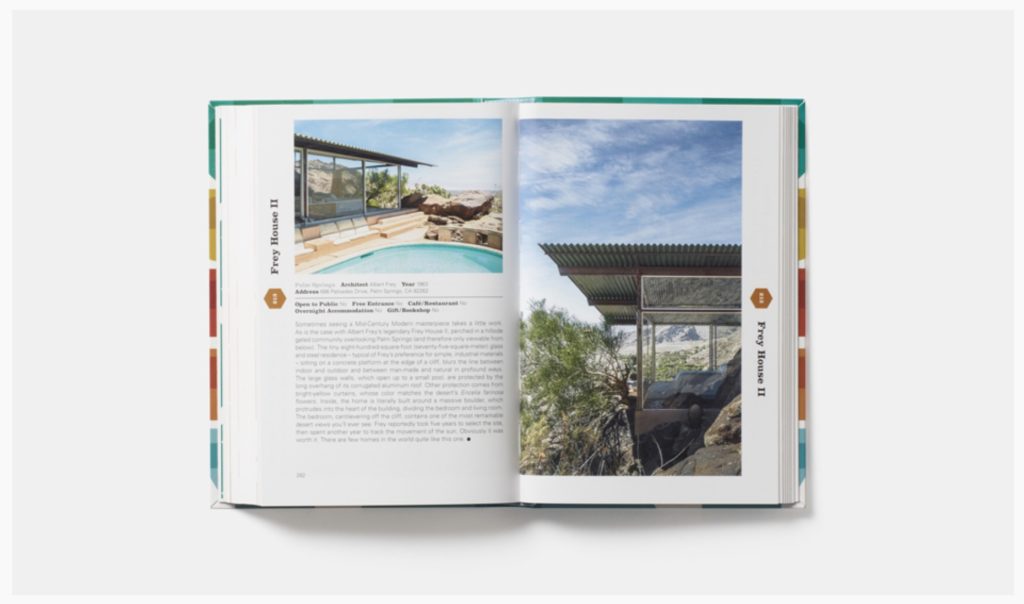

Your recent Mid Century Modern travel guide(s) seem to have been very well received. What was the production process like for these books? You covered an incredible amount of ground and so many subjects all over the country, and even won a few awards in the process.

It was pretty much the same process for both our West Coast and East Coast books. My partner Sam Lubell and I started out with a spreadsheet that we just added projects to, as they came to mind or we discovered stuff. We’d also reach out to local experts in each region. We would get together in person or on the phone every few weeks to talk about what we’d added. This went on for a period of about three or four months. We were also sharing our list with our editors at Phaidon, and meeting with them periodically for their input.

Once we had a fairly complete list, I generated a master Google Map with pins in each location. I would check Street View to verify that the project was visible from the street and still in good shape, and also tried to get an idea for best time of day to shoot it. Then I mapped out what was doable by day, breaking down each day into increments to account for shooting and travel time between each location. Phaidon wanted only daylight shots, so we tried to do as much travelling as possible at night, and use our daylight hours to shoot in a specific city, or region. It was all very carefully planned. Of course, no plan ever survives first contact with the enemy, and that was true here, too.

To put it mildly, there were lots of challenges with this approach. We never knew exactly what we’d find as we rolled up to these places, despite all the planning. Murphy’s Law struck more often than not, and a lot of projects were overgrown with shrubs, or surrounded by construction fencing or scaffolding, or crappy vinyl signage, or delivery vans parked out front, etc. And the weather often failed to cooperate. If we got delayed on a project, it could throw us off by a whole day, as we needed to get everything in a city before moving on. It was often impossible to go back. And since things did move around a bit, as we adapted the schedule to circumstances, it was impossible to coordinate in advance with people at each site. We just had to wing it. Most people we met were amazing, and very welcoming.

Shooting just a few photos for each of the 300 projects in 300 different sites across thousands of miles is a very different thing from spending a day or two shooting a single project, as I do most of the time. You need to work quickly, and improvise, and have no control over your environment.

We also had to stay flexible because we found lots of projects while simply driving around. Many of those also ended up in the books.

Once we had the photos, Phaidon stepped in more actively, and reviewed what we had. We came to common agreement on what stayed in and what had to be left out. And then I finished editing photos, and Sam set to writing each description. It was truly a collaborative project from start to finish, for each book.

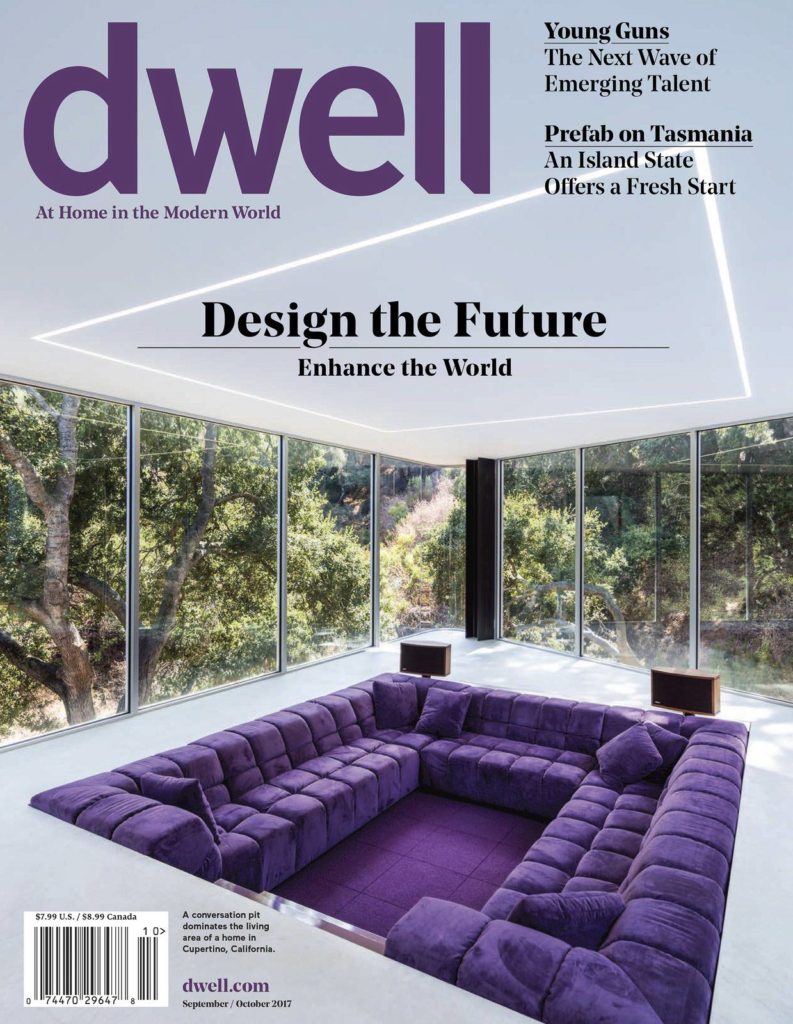

You recently nailed the cover of Dwell with your images of Craig Steely’s stunning “Pam & Paul’s House” – congratulations! Walk us through your thought process a little on that shoot – did you know it had cover potential as you were shooting?

“Pam & Paul’s House” is a clean, glass, minimalist white box suspended over a canyon. Most people remember it as “the Purple Conversation Pit House”. Craig is such a talented architect, and his projects are always so original, visually striking, and editorial. They’re very photogenic, so there’s not a lot that I need to do, really. As long as I don’t screw it up, I think it’s a pretty safe bet that the project is going to get published. I definitely knew that the house had cover potential when I was shooting… But I never would have guessed which photo they’d use. I’m usually a pretty poor judge of which photos a client will end up using, from the selections I provide.

You gave a freakin’ TED talk – one of only a few photographers to have done so, certainly rare air. I don’t imagine I’ll get to ask this question often, so what was the process like? How did you decide on a topic, prepare, and get ready for it? Any regrets about the talk, or things you’d do differently?

I was living part-time in Canberra, Australia, back in 2016/2017, and was spending my spare time there photographing and researching the local mid-century modern architecture. I was then invited to give a lecture there to show my photos and share what I’d learned with the locals. It turns out that some of the organizers from TEDxCanberra were in the audience and heard my talk. So they invited me to participate in the TED program.

I’ve seen lots of TED talks, but honestly didn’t know anything about the process before I took part. For the first session, I didn’t even realize that it was a sort of try-out. Everyone else there was nervous, huddled in a corner somewhere rehearsing their lines to themselves and waiting for their audition. Naively, I just showed up thinking it was already a sure thing, and had nothing prepared. But I was able to wing it for the audition and did get selected in the end, so it worked out. I probably came across as arrogant, but I was just clueless.

It’s a long process, where you are assigned a speaking coach, and there are several sessions with the team and the other speakers, where they help you to develop your topic and give you tips, and you get to know the other speakers. But because I was shuttling back and forth between Australia and the US, I missed some of those sessions.

The theme of my talk was similar to the earlier talk. I wanted to show Australia (and the rest of the world) what was special and significant about the Modernist architecture in Canberra, and how it was relevant to the rest of the world. I was really just trying to get people to appreciate and preserve more of the buildings from that time period.

Because my talk was so visual, I didn’t rehearse a script like the other speakers did. I just showed my photos and used those as prompts for what I wanted to say. I’m not sure what I would have done differently. It was hugely rewarding and I am still friends with many of the speakers and organizers. I am used to speaking in public, but this was a very different experience and was a lot of fun.

You’re the absolute champion of architectural selfies – is this something you do out of necessity, humor, or both? I enjoy playing ‘Where’s Darren’ when when you post new images!

That was sort of an accident, really. Architectural photography is typically a solitary activity – especially when I’m just out shooting for fun. Normally, I set up a shot and just wait for people to walk through my composition. But when there’s nobody around – or the people aren’t positioned where I’d like them to be – I sometimes just put myself in the shot, using a timer. At least it started out that way. Now, it’s become a bit of a running joke, like how Alfred Hitchcock would always do a cameo in his films. It’s fun for me, but I try not to overdo it.

Lastly, for the gear nerds out there: what’s your standard go-to setup?

I have lots of cameras and setups, depending on the project and the occasion. But my standard setup is typically a pair of Canon 5dsr bodies and related tilt-shift lenses (45mm, 24mm, and 17mm). I use the 17 most, by far. I rarely shoot tethered, unless I have a client with me who asks me to. I like to shoot quickly, and I’m constantly watching the light as it changes. I don’t want a lot of gear to slow me down, as I miss shots that way. I also rarely use lighting these days – I used to use a set of three Omni hot lights a lot, and the occasional strobe. But again, it slows me down and I rarely find the need anymore, with digital camera technology what it is. It’s still useful sometimes, to mimic sunlight or illuminate a dark area, but it’s no longer a de facto thing. I am almost always shooting on a tripod for commissioned work, though, and have a couple of RRS and Gitzo tripods that I use, in various sizes.

When I’m traveling for myself, I often don’t bring a tripod. But I do bring a fairly beefy travel camera: a Fuji GFX-50S medium format camera, with an adapter a Canon 11-24mm zoom. It’s bulky and weighs a lot, but it’s a great setup for shooting architecture hand-held. Eliminating the need for a tripod means it’s lighter than I would normally bring, so it’s still a “travel camera” for me.

Either way, I travel very light and have a small footprint. Clients are often surprised when I don’t show up with multiple Pelican cases full of gear, and some are probably disappointed. But likely because of how I got started, just shooting stuff as an amateur and running from security guards, I’ve always tried to avoid carrying a lot of gear.

At the end of the day, it’s about the architecture – not the gear.

A million thanks to Darren Bradley for taking the time to tell us about his life and career. His work can be seen on his website, and be sure to follow him on instagram.