How To Create An Architecture Photography Book: Part One

For some reason photographers are obsessed with being published, I am a photographer, ergo, am obsessed with being published. It feels good, it looks pretty, and it makes your photographs real, as in a tangible thing that other people hold and look at and say “wow” like Owen Wilson. Wowwww.

I’ve had my photographs in countless books, plenty of magazines, endless newspapers, etc, but when I got an email from Prestel, a subsidiary of Penguin/Random House back in late 2017 (holy smokes, I can’t believe it’s been that long) I was particularly excited. I mean, just look at my punchable face in the lead image! I am/was psyched.

The email mentioned that they were searching for a photographer in Los Angeles to create new images of 50 of Los Angeles’ most important pieces of modern architecture for a book (here’s a link to the actual finished book – check it out) that would be exclusively photographed by me, and distributed around the world by them…Um, yes please. That kind of opportunity comes rather rarely and usually at a point where a photographer or artist has actually established themselves (I mean give me a break, this is not even my tenth year in business, but my imposter syndrome is beginning to go away so we might be making progress).

Before I spoke further with the publisher, I knew the answer was yes. Didn’t matter how much they were paying, how much time it would take (hint: a lot) or how much it would disrupt business in the short term (another hint: even more), I absolutely had to do it.

1) The Brief

Pretty simple. The goal was to photograph 50 of the most important pieces of new architecture in Los Angeles. The publisher had a rough idea of what they wanted captured – homes, apartments, concert halls, courthouses, high rises, police stations, whatever – they were all in there. I provided some input and helped guide the final location selections based on my experience of living in LA and interacting with many of the locations on a semi-regular basis. I also guided selections based on practicality and first-hand knowledge of how the general public of Los Angeles had responded to the buildings. There were a few examples of projects that were great on paper but not well maintained or not very successful after their initial praise for a multitude of reasons, so we decided to cut them after preliminary photography returned disappointing results.

Many buildings were also in somewhat shady areas. It’s one thing to see pictures of a fancy new apartment building on ArchDaily and another to visit it five years later without clients or an escort and whip out a camera in a rough area (skid row is tragic, believe me – it’s also not the place for a lanky doofus like me to gallivant around with $10k in cameras around my neck). I’ve had more than my fair share of troubled individuals get irrationally angry at me to the point of physical violence that I just won’t go in and shoot in some of these areas alone anymore. If you’re familiar with Los Angeles, you kinda know what I mean.

We also needed to obtain permission and support in many cases. “Roll up to a public middle school and start taking pictures” is probably not the brightest idea in this day and age. Neither is “go try and take pictures of the Rampart police station” but that’s neither here nor there – a significant chunk of time was securing permits, making contacts, and providing COIs to get into these locations. Most of the time we were able to get in touch with the architect of the building who would be happy to work with us to get us access, and in some cases where the architect no longer had a working relationship with the tenant we were able to let them know that they’d be getting some good press and a few copies of the book and they were happy to oblige. Patience was the name of the game as some locations took months to get through this process with multiple pieces of paperwork floating in the void between email addresses. Many things were probably better done with a “beg forgiveness rather than seek permission” attitude in hindsight, but in the end I’m glad we did everything the right way and everyone was happy with the outcome.

2) The contract

A pretty typical arrangement for books is an advance which finances the creation of the book followed by royalties for every copy sold once the advance is paid back. I was able to share behind the scenes videos and images while production was in process (which was great for my instagram validation, can’t live without it) but not able to share any final stills selected for the book until the release. That…was by far…the hardest part. We started shooting in November of 2017, wrapped final post production in June of 2018, and I’ve not been able to share anything until April 18th of 2019. Argh!

The contract otherwise was quite reasonable. I owned all images, retained copyright, and licensed the images to the publisher for the book itself and promotion of the book. Piece of cake, to be honest, and very straightforward. I appreciated their desire to keep the photographer in control and respect copyright, etc, in a world where this is constantly being eroded.

3) The plan

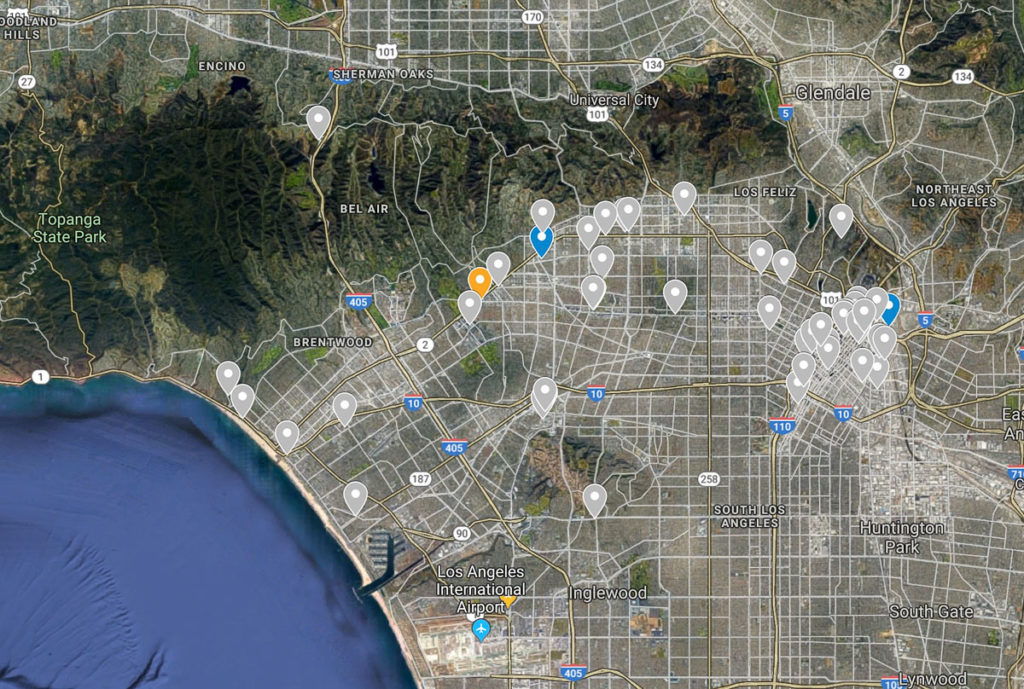

After narrowing our locations down to 50, I mapped them all using a shareable Google map. From there, I would plan each shoot based on where the sun would be, choosing favorable times of day depending on the exposure that each building got – full sun, no sun, etc. Some buildings got light on the facade during the morning, so they were morning shoots, some in the afternoon, and in some cases, where time of day didn’t really matter, it was noted in the map. Some projects were all-day or multi-day affairs requiring multiple trips – which was also noted. The Google map was great as I was able to share real-time updates with the publisher and would categorize each shoot as we went: scheduled, in progress/needs more images, and totally done. Anyone could go in and edit the map if locations or dates changed, add notes about access, or add general questions. Since I just grabbed a screen capture, most locations are greyed out (that was code for “photography completed!”)

Once I had an idea of what I had to shoot and when I wanted to shoot it, we could approach each individual location to secure permissions, permits, etc. Some of the spaces were totally public and didn’t need any permissions, and I tended to front load these in the calendar so I could get some momentum. I could then schedule the more restrictive shoots later, working around my contacts/client schedules to make it easier for everyone. One thing is for sure and that is you can’t be demanding when people are doing you a favor, so I tried to be as flexible as possible when people were helping us out with access. In the end this worked out fantastically, and we only had one location out of 50 give us a hard no – it was a fruity tech giant that used to make great laptops, who, for reasons, wouldn’t allow it even though pictures of that project exist all. over. the. internet. Whatever – their loss, as they were replaced with another great project who was happy to facilitate us!

4) My business

…Was more or less permanently offline for three months. In fact, it was the only quarter in my history of being a photographer that I failed to make any profit at all. I had half of the advance but still had payroll and some minor overhead to deal with, which ended up putting me in a $10k hole for the first quarter of 2018. But to be completely honest there is no way that I’d be able to do this and give it my full attention if I was taking on other client work in the meantime. 50 shoots is A TON of work – even spread over three months – considering that I had to return to multiple locations more than once due to weather, construction, traffic, and general shenanigans (mostly me just wanting to take better images). Even when I had a rare day off, I’d at least usually go and make a couple pictures to improve upon what I’d already created at some locations. True days off were almost non-existent.

By the end, I was completely drained, and I hadn’t even begun post production yet. In part two, we’ll jump into the actual shooting process, and I’ll explain my thought process for photographing some of my favorite locations. Stay tuned…

New Architecture Los Angeles is available for order at many trusted booksellers. Pick it up to see the final product!

For the rest of the book saga, you can read the other parts here:

How To Create An Architecture Photography Book: Part One

How To Create An Architecture Photography Book: Part Two

How To Create An Architecture Photography Book: Part Three

How To Create An Architecture Photography Book: Part Four