Roland Miller Discusses Photographing The Interiors Of The International Space Station

Roland Miller is a documentary and fine art photographer hailing from Chicago, Illinois. He has been documenting the various test and launch sites NASA and the United States Air Force had developed for the early space missions (Gemini and Apollo) for 30 years. Partway through this journey caught the attention of NASA that gave Roland unprecedented access to some of its projects. I caught up with Roland to talk about his latest work on photographing the interiors of the International Space Station from terra firma.

Hi Roland, thanks for taking the time for this interview. To begin with, you are Chicago native and have been photographing for over 30 years. You have been heavily involved in the academia aspect of photography only having retired from academia in 2018. Can you give us a highlight into your career?

I got into photography through working for a hot air balloonist in the mid-1970s. I enjoyed photography from an early age, and hot air ballooning provided a unique subject, especially at the time. I majored in Art and photography at Utah State University and received both my BFA and MFA in Art. Shortly after graduated, I started teaching photography at Brevard Community College (now Eastern Florida State College) in Cocoa, Florida—right by the Kennedy Space Center and Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. I was there for 16 years, and it rekindled my childhood interest—love really—for space exploration. I moved away when I got married and taught photography at the College of Lake County, in Illinois for another six years before becoming dean of the Communication Arts, Humanities, and Fine Arts Division for another ten years. I retired from higher education in 2018, and I have been working on photography full-time since that point.

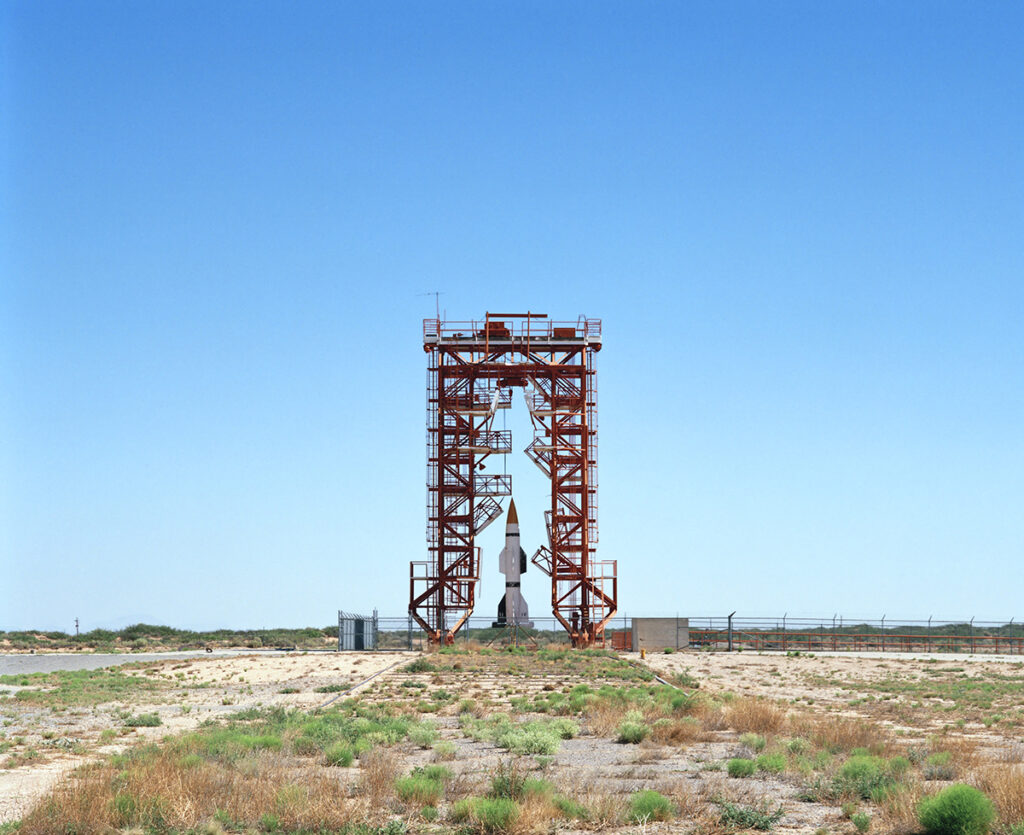

In graduate school, I worked on colour landscape photography. While out and about making landscape photographs, I started exploring the interiors of abandoned farm and ranch houses in northern Utah and Southern Idaho. Though not directly part of my graduate school research, this subject somewhat took over my photography. As it turned out, producing that body of work (which I titled Interiors) was the perfect preparation for photographing the deactivated and abandoned space launch and test facilities I investigated in my project, Abandoned in Place. There was a continuity to the materials and décor of the old ranch houses in the specific locales. You would see the same paint colours, wallpapers, and linoleum in homes in these small towns. There was an archaeological quality to these visual investigations—though my main interest was exploring the light and colours in these pre-World War II structures.

In 2003, I was conducting a photography workshop at Casper College in Wyoming with a couple of friends and fellow photography professors, Todd Bertolaet and Denis Defibaugh. We took the students on a field trip to several small Wyoming towns. I had one of those fantastic days where you see things in a way you haven’t seen them before. I quickly realized that there were continuity and a theme to the images I was making which resulted in the Real West project. Real West is an ongoing project where I juxtapose modern constructions in contemporary scenes with traditional western iconography. Real West is still a work in progress.

You have been documenting deactivated space launch and test facilities across the US for over 25 years. What was your motivation in embarking on such a long documentary project, especially in space exploration?

While I was working at Brevard Community College, I received a phone call from an environmental engineer at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. He had found an old darkroom in a somewhat abandoned building out there, and he wanted my help in properly disposing of the old photographic chemicals. In the process of that work, he took me to Launch Complex 19—the Gemini Program launch site which lay dormant for over 20 years. The minute I saw it, I knew I had to photograph it. As it turned out, there were many other old, unused launch pads on Cape Canaveral Air Force Station. Part of the reason the project lasted so long is that the Air Force kept decommissioning launch complexes. At that point, I would go in and photograph them, sometimes even during demolition.

It took about two years from the time I visited Complex 19 until I could get the kind of access I wanted. I wanted to work with an 8 X 10 camera—and I did do some work in that format. Unfortunately, the Air Force Public Affairs officials were used to working with photojournalists who needed to get their shots taken fast and get their photos in for publication. That’s a grand oversimplification of photojournalism, and I’m not trying to condescending. I’d be hard-pressed to be a photojournalist. Suffice to say I work A LOT slower than most photojournalists.

I was finally able to meet with representatives from NASA Public Affairs at the neighbouring Kennedy Space Center and explain the type of work I wanted to attempt. They allowed me to make a few escorted trips to photograph he old NASA pads on Cape Canaveral as a sort of demonstration. Once I showed NASA and the Air Force that original body of photographs, they were both very supportive and helped me make arrangements to access these secure facilities. Once I had made a good impression with the NASA Public Affairs officials, they introduced me to the other NASA facilities.

I have been photographing these space subjects in a hybrid documentary/abstract approach, which sounds contradictory. More specifically, I record overall scenes to give it context. Furthermore, I make selective detail images that isolate small portions of the whole subject. My goal is to provide a broad experience of the subject and not expansive or close-up perspectives. In turn, giving the viewer the ability to observe details, like signs, wording, labels, and details otherwise overlooked. In addition to all of this, I’m trying to make visually appealing imagery. This became the foundation of my work in the book, Abandoned in Place.

You’ve had excellent access to NASA’s programs including photographing components of the ISS in 1998 and documenting the entire Space Shuttle. How did your relationship with NASA come to be, allowing you to undertake the projects as mentioned earlier?

My relationship with NASA developed through my work on Abandoned in Place. The work was well-liked by my contacts at NASA, and I like to think they saw it as something that no one else was recording, at least in the same manner. I approached NASA in 2008 with a proposal to interpret the final years of the Space Shuttle Program with my photography. I’m sure it was the Abandoned in Place body of work that helped them to agree to the project.

Your most recent work on the ISS (Interior Space: A Visual Exploration of the International Space Station,”) was inspired by the collaboration between Astronaut Catherine Coleman and musician Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull) to celebrate Yuri Gagarin’s 50th Anniversary. How did you approach this project to sell it to NASA?

In 1999, Catherine Coleman(Cady) was staying at the Astronaut Crew Quarters on the Kennedy Space Center, where astronauts reside during training and before launch. Some of my Abandoned in Place photographs were on display at the crew quarters. Cady saw this body of photographs and left a message on my work voicemail saying how much she enjoyed the images. She said her husband was an artist (Josh Simpson is a well-known glass artist). When I returned to my office, I tried to contact Cady, but she had gone back to Houston.

Fast forward 15 years. I attended the maiden launch of the new Orion spacecraft on a Delta IV Heavy rocket in 2014. It was un-crewed, but NASA sent four astronauts down to interact with the press before and after the launch. Cady was one of those astronauts. I introduced myself to Cady, and she remembered my photographs. Cady wished there was a way to get my photographic approach and vision to astronauts on the International Space Station. She asked me to think of how I could accomplish that.

In researching this idea, I discovered that Cady, an accomplished flute player, had performed a duet with fellow flute player, Ian Anderson (from the band, Jethro Tull). At the same time, she was onboard the ISS, and he was performing at a concert in Russia in honour of the 50th Anniversary of Yuri Gagarin’s first human spaceflight. It gave me the idea that I could do something similar with an astronaut on the ISS and myself on the ground. I wrote up a proposal to work in real-time with an astronaut to photograph in my hybrid style. Cady liked it, and she connected me with Italian astronaut, Paolo Nespoli, who had been on Expeditions 26 and 27 to the ISS with Cady. Paolo was returning to the ISS in about seven months. Paolo liked the idea, and he realized that working in real-time would be prohibitive and recommended we work asynchronously by emailing images back and forth.

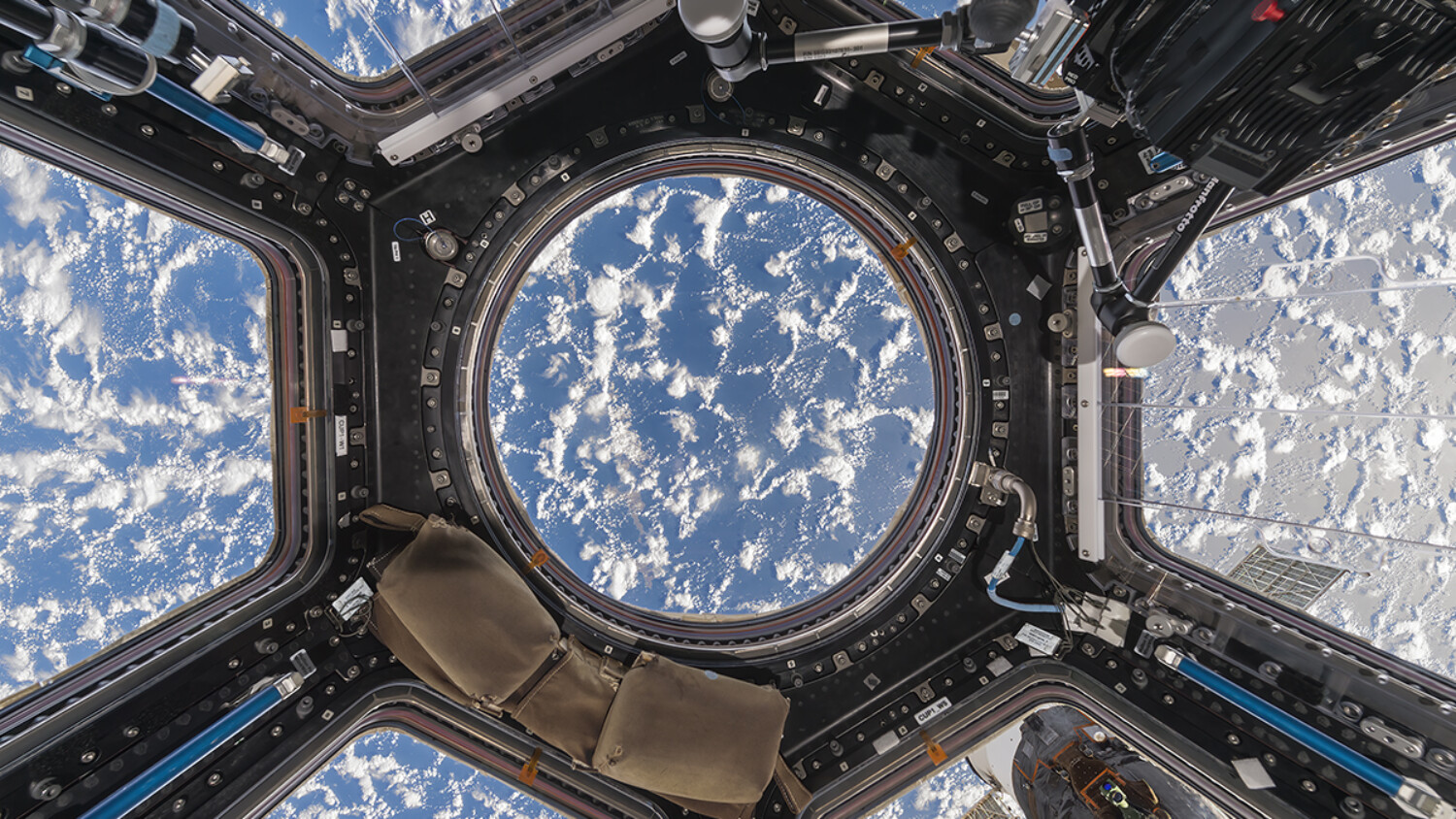

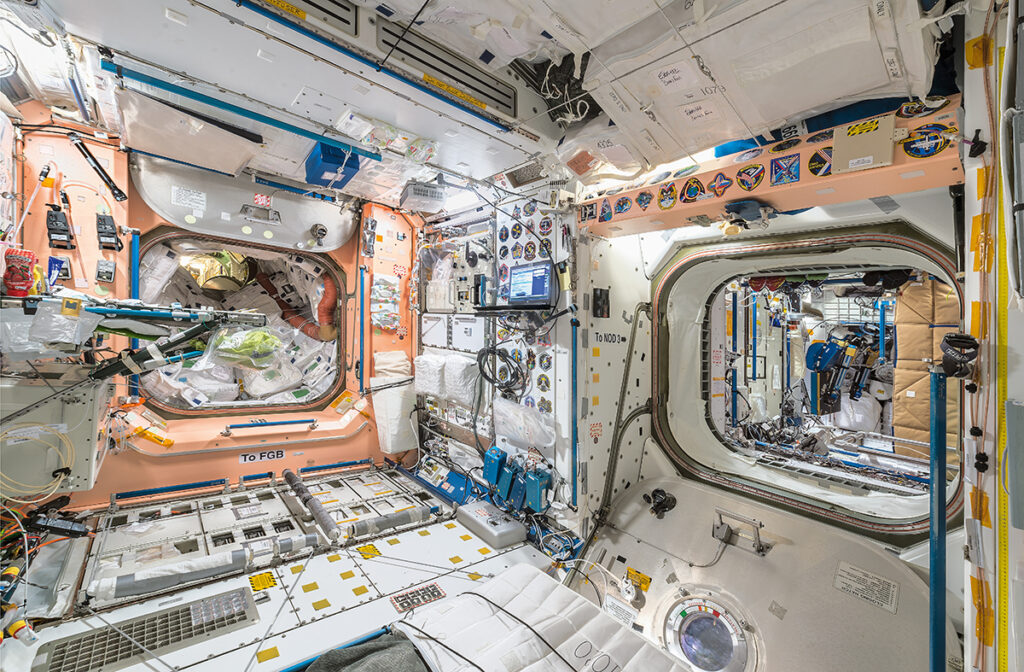

My proposal consisted of studying existing imagery from the ISS, photographing the ISS mockup at the Space Vehicle Mockup Facility at the Johnson Space Center, and then directing the ISS photography. I wanted to create photographs that weren’t part of the standard photography on the ISS. It became clear to me that the astronauts were outstanding photographers, so trying to “outdo” them with the imagery they were already making seemed pointless. Most of the photography was images of Earth made from the Cupola or other viewing ports on the ISS. Again, this imagery was exceptional. The bulk of the other photographs were of experiments or the astronauts performing tasks. There were not many images of just the interior of the station itself. I felt if we, Paolo and I, could photograph the interior of the station with mainly available light, we could give viewers a better sense of what it looked like to be on the station. This approach also fits with both my technical and aesthetic methodology.

Cady’s main contributions, (both essential), were to challenge me to attempt something this remotely possible and to connect me with Paolo. It turned out that Paolo was the perfect partner. He is a skilled photographer with more experience than most astronauts. His knowledge of spaceflight and the International Space station, in particular, were invaluable in the success of the project.

How did you familiarise yourself with the entire ISS to know what you wanted to photograph?

I spent six months studying every image of the station interior I could find. As luck would have it, NASA and Google released a “Street View” of the ISS interior a day after I photographed the mockup at the Johnson Space Center. The “Street View” proved invaluable since I could make screen captures of what I wanted Paolo to photograph with secondary instructions and send these to him to create my desired compositions.

Before this project, you have spent years documenting various projects about space travel, with all those years of experience and perfection of your craft, how did you transfer this knowledge to Paolo in order make it look like you were in the ISS?

First, we believe this is the first true collaboration between a visual artist on Earth and an astronaut in space. I used the Google Street View of the ISS interior to make screen captures of what I wanted Paolo to photograph. I would markup or add instructions to these screen captures and email them to Paolo in orbit for him to create my desired compositions. I wanted Paolo to use his insight to make on the spot adjustments to the image templates I sent him. Still, it was almost eerie how the images felt like my own photography.

Can you share the technical aspects of the project that you had to give much thought to ensure its success?

Though my technical approach was suitable for showing the inside of the ISS more as it looked (rather than with on-camera flash), it was not a simple method of working in a microgravity environment. On Earth, the majority of my work involves the camera on a tripod. Tripods don’t work in space—they are weightless too. Again, Paolo was an excellent partner, because, on his own, he devised a method of connecting two of the “Bogen arms”—the articulated arms that hold laptops and other equipment when attached to station handrails—to the camera by scrounging up an utilized adaptor. The arm allowed him to stabilize the camera at two points which were enough to allow for a low ISO and slow shutter speeds.

I expected Paolo to shoot between 1000 and 3200 ISO. But his bipod allowed him to photograph as low as 100 ISO, my preferred setting. At the end of his mission, he made a good number of photographs handheld at around 1000 ISO with shutter speeds between 1/15th and 1 second. These final images were blurrier and noisier than the other photographs. I utilized Topaz Sharpen AI and Denoise AI software to align the image quality with the earlier photographs Paolo made.

You launched this project on Kickstarter, which has seen you surpass the required funding level. What has been the initial reaction so far to the book?

I had done a Kickstarter campaign for Abandoned in Place, and along with raising funds to offset costs related to the project, it drew a fair amount of attention to the book. I felt it would be good to do the same with Interior Space. The Kickstarter campaign for Interior Space has had overwhelming support to-date. The book and rewards which are listed on the campaign have been received very well.

The book is being published Damiani Editore, as Damiani is well-known for their beautifully designed and printed art and photography books. Because Paolo is Italian, it seemed like a perfect fit. Despite, the pandemic, the book is on track for deliveries in October.

You can see more of Roland’s work on his website and additionally follow him on Instagram.