Christopher Payne’s Remarkable Work Celebrates the Beauty of Manufacturing and Design

Throughout our careers we find photographers and artists who inspire us at a deep level, and I am so happy to be able to bring you an interview with one such photographer today. Christopher Payne, who was educated as and practiced as an architect, has long been one of my favorites not only for his prowess as an architectural photographer but as an embodiment of the personal project and its ability to bring incredible opportunity for pursuing one’s interests, exploring incredible places, and shaping your career into something entirely your own.

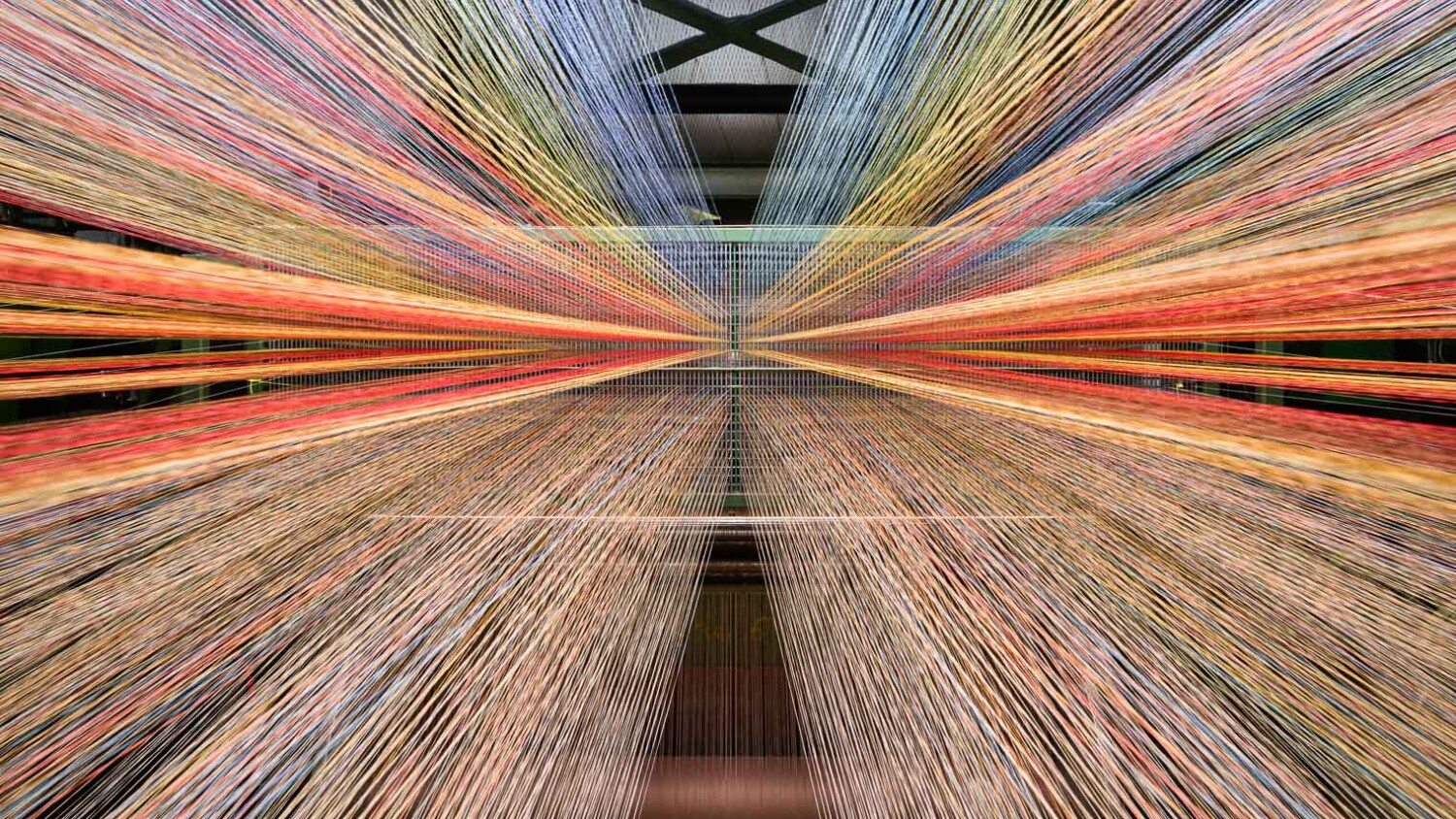

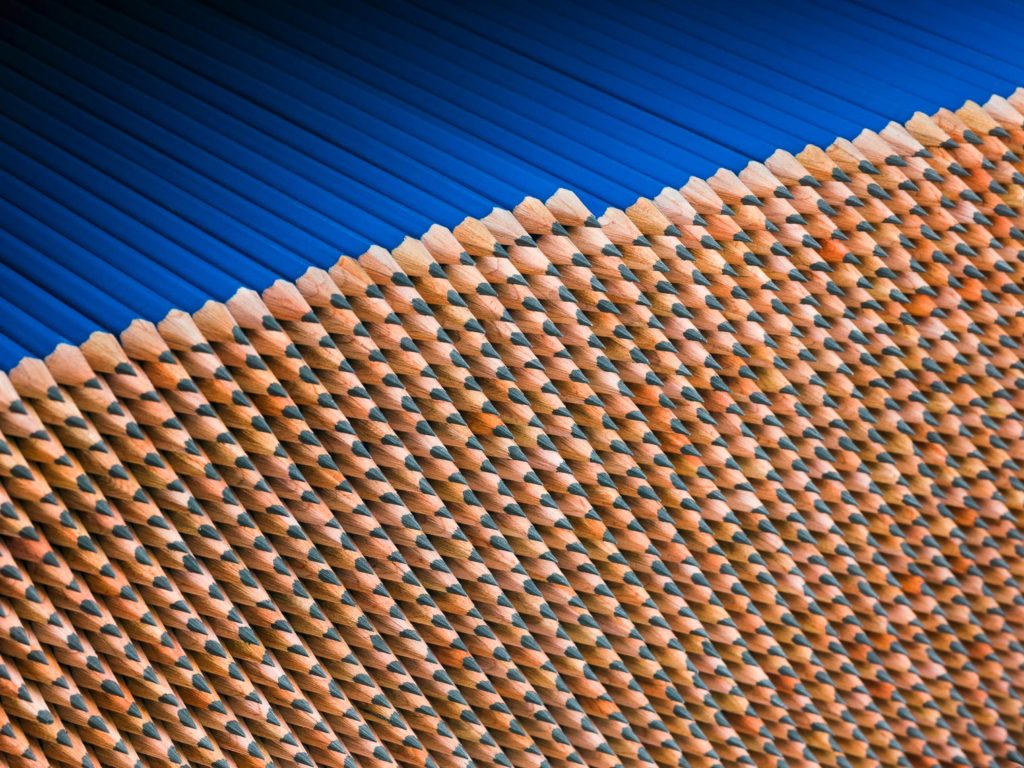

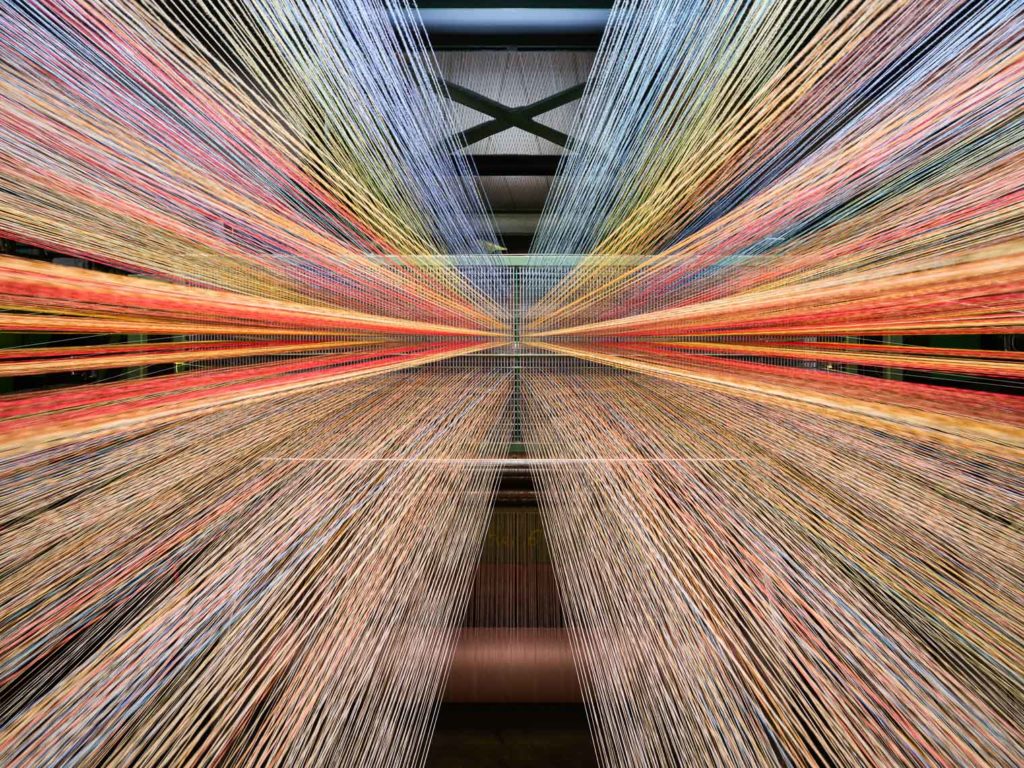

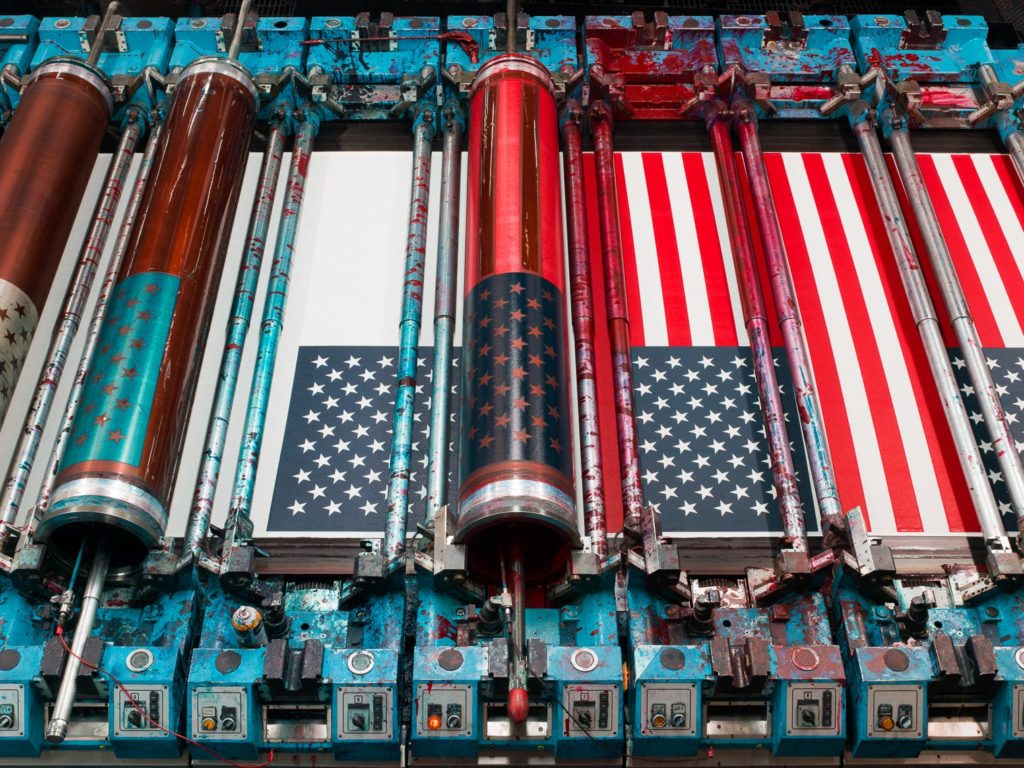

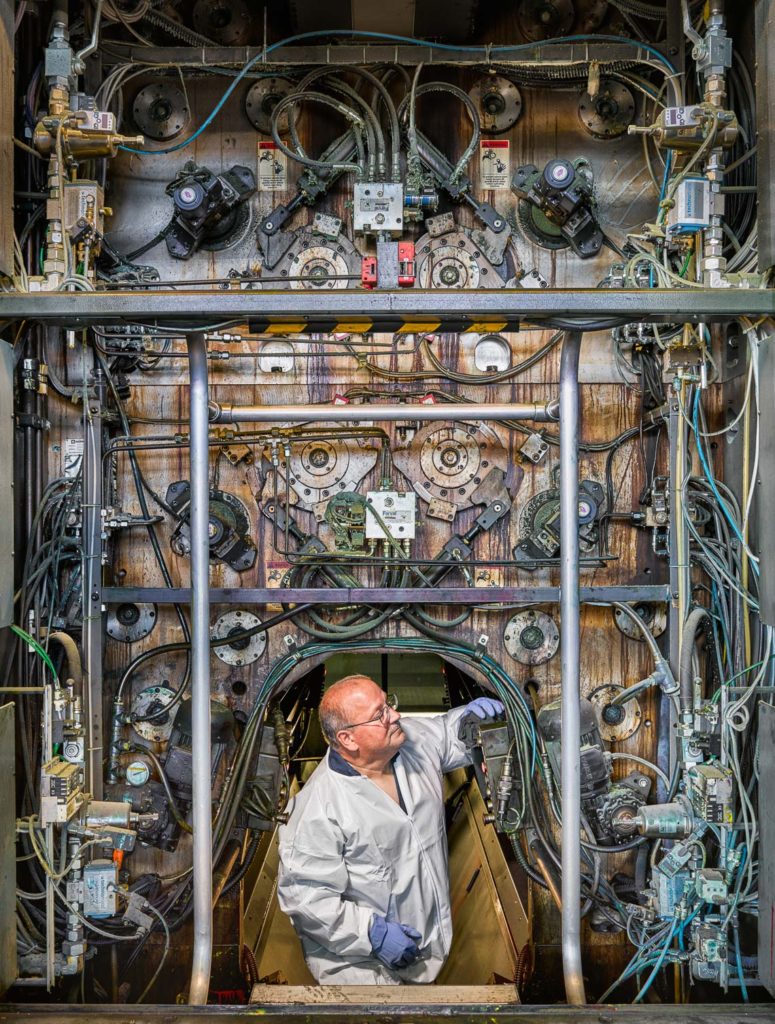

I remember the first time I saw Payne’s work like it was yesterday; it was so startlingly fresh and evocative. His use of lighting and composition is instantly recognizable, though it has absolutely evolved over the years throughout his archive of projects. His subjects are almost entirely his, as in, once you see a series and understand the subject, usually a gritty factory distilled into a beautiful scene full of rhythm and order, you think “of course Christopher Payne shot that!” once you see the credit line.

He’s become one of the foremost photographers documenting human craft and industry. Instead of focusing on the, honestly, cliche and over-wrought “human condition” or “the way humans have shaped the environment” (how many times have we heard that one?) Payne has celebrated the process and talent used in creating some of the most iconic products the world has ever seen, and his work is utterly remarkable for it. Have I gushed enough yet? I hope you find this insight into his work as fascinating as I have – and that you walk away inspired to pursue your own personal work with an excitement that is so obvious that it bleeds into your images like it does with Payne’s.

Hi Chris, so excited you’ve agreed to be interviewed. To start, I noticed that you were trained as an architect; how and why did you make the jump to photography, and how do you think your architectural background informs your work? I absolutely see an architect’s eye in the images in many of your compositional choices, but I’d be interested in knowing if it changes how you approach the subject matter as well.

I taught myself photography when I was writing my first book, New York’s Forgotten Substations: The Power Behind the Subway. The project began as a collection of drawings I was making of old transit substations and their electrical equipment. I rarely had time to finish the drawings on site, so I took snapshots to help me complete them later at home. Over time, I found myself enjoying the preparation and taking of these pictures more than I did the drawings, and I knew I had found my true calling. It took another six years to make the career change but it’s the best decision I ever made.

My architectural background plays a huge role in my approach to photography, from the structured way I compose my pictures to the subjects I photograph. I am naturally drawn to the built environment and processes of design and assembly. I think of my photographs as architectural drawings that serve as visual aids to explain how things work. In my first books, Substations and Asylum, it was necessary to recreate for the viewer a whole that could only be assembled from parts that survived here and there, across the country or across the city. With Making Steinway it was the opposite, a deconstruction of something we all know and love as a whole into its unseen, constituent parts.

From the outside, it looks like your career has been one long personal project; your ability to photograph projects that you are passionate about is inspiring and I can absolutely tell you care very deeply about what you photograph. Have you always only photographed things that you were passionate about, or do you balance this with regular commissioned commercial work that “pays the bills” but perhaps you don’t feel so attached to?

For the past ten years I’ve worked as a commercial architectural photographer and this has funded much of my personal work. I’ve also been fortunate to receive editorial assignments and industrial commissions that align with my personal interests. It’s a constant juggling act, trying to find the right balance between making art and making money. As much as I wish I could focus on my own projects all the time, I enjoy the collaboration with architects and editors, and the variety of subjects makes me a better photographer.

Do you often attempt to create a photo project solely because you’re interested in it and you approach publications with an idea in mind, or do the projects come to you? Knowing that you are a specialist, shall I say, industrial photographer, you have a reputation for this work at this point and I’m assuming you get many requests but am curious if you still have to do the legwork of coming up with the ideas and sending pitches.

I am always thinking of projects to pitch and creative ways to pitch them, knowing that editors are hungry for fresh content and that it’s much easier to gain access to a factory when the request comes from a magazine. If no one is interested but I’m passionate about the idea, I will pursue it independently and try to get it published later. The benefit of this is that I have creative control and can work at my own pace.

What is the biggest “oh shit” moment that you’ve faced on a shoot – and how did you overcome it? You must have some incredible stories from photographing such a wide array of locations in many different parts of the world.

In 2018 I was commissioned by the New York Times Magazine to photograph a candy factory in Colombia. The place was enormous, full of intoxicating sights, sounds, and smells—a real life version of Willy Wonka’s factory. Back at the hotel I panicked as I poured through the dozens of scouting shots, not knowing where to begin and fearing I wouldn’t have enough time. The editor offered this simple advice: “Focus on the beautiful,” which freed me of the burden of feeling like I had to document everything. There were many interesting things in the factory, but only a fraction were both photogenic and specific to the process of making candy. Being able to filter out the extraneous, to quickly assess what’s essential and what’s not, has proved invaluable many times since.

How do you prefer to shoot – slow and calculated, or rapid fire with a protracted cull back in your studio? Your projects all have such a tight narrative and I’m wondering if you are planning everything very deliberately with scouting ahead of time, or if you are waiting until you get on location to see what you find and improvising as you go. I imagine access can be quite tight as some of these locations so I find this particularly interesting.

Having learned photography on a 4×5 camera, I prefer a slow and calculated approach. If I have time, as I did with the pencils and the Daily Miracle, I will let the work evolve organically until I am satisfied with the results or no longer inspired. It’s not unusual for me to meditate on a particular shot for months and reshoot it several times. For most editorial and commercial assignments, I am not afforded this luxury so I try to scout the location first. On the extreme end, I recently photographed a satellite factory in Denver that was housed in a restricted clean room, and prior access was not possible. After donning a special suit and having my equipment wiped down, I was granted just a few hours for the entire shoot.

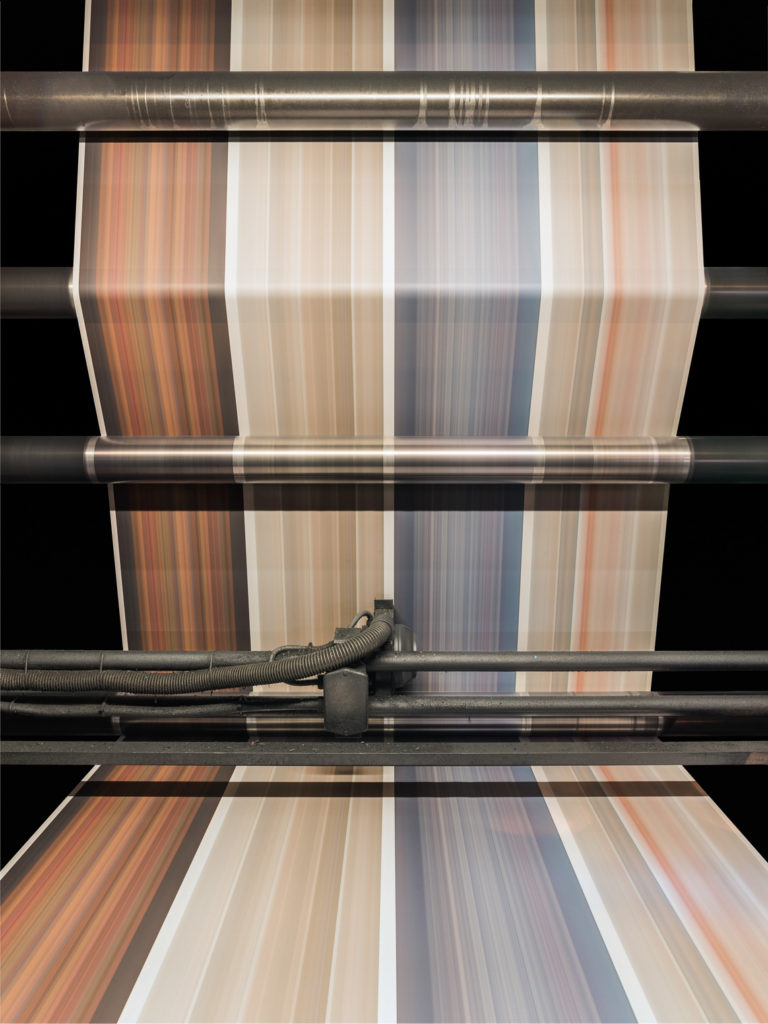

Your New York Times series “The Daily Miracle” is unbelievable; probably one of the most inspiring that I’ve ever seen. Can you walk us through how this job came to be, the process of photographing it, and how you feel about the finished result? I am sure there was a lot that was out of your hands but you managed to tell the story so well, and the compositions you found were brilliant.

The Daily Miracle was a long term personal project and it took two years to gain access to the printing plant. This was by far the most challenging place I’ve ever photographed. It was vast, chaotic, and visually overwhelming. If I came away with one or two good pictures per visit, I was happy. Sometimes I would walk around for hours, only to leave empty handed and demoralized. By the time the photo essay was published, I had made forty visits.

Upon arrival, I would walk down a hall lined with black and white photos of the original printing plant in Times Square, circa 1950. I was inspired by these classic scenes, which looked like stills from a Hollywood movie, but also frustrated because I knew I couldn’t recreate their vintage look and feel. Nonetheless, I am especially proud of this series because I pushed myself creatively to produce a fresh body of work that celebrates the present technology and the pressmen without seeming nostalgic.

A big thank you to Chris for letting us take a peek into his process and sharing these fabulous images with us. You can see his website here, and be sure to give him a follow on instagram here.

Below are further information and links to Payne’s projects, both personal and commissioned.

Candy – NYT Magazine (commissioned)

Daily Miracle – NYT Magazine (personal)

Textiles – NYT Magazine (personal)

Still At It – NYT Magazine (personal, evolved into a commission)

Golf Balls – Golf Digest (commission)

Gamblin – a commission that turned into a personal feature for Topic