Meet Denmark Based Architect, Artist, and Photographer Mikkel Frost

Mikkel Frost is an exceptional architect and co-founder of the Danish architecture firm CEBRA. When not “working,” Mikkel is well known in the architecture scene for his lively sketches and watercolors. What people might not know is that Mikkel is also an avid photographer, taking many of the pictures for his office. In this interview, Mikkel and I get into themes like photo taking, monkey method, Adam Mørk, Nikon F3, and much more.

I met Mikkel when I worked as an intern at CEBRA in 2009. He was the one who taught me the importance of keeping vertical lines straight. At that time we didn’t talk about photography but the art of architectural renderings, which for architects, have many similarities to photography such as story, composition, light, and texture.

In 2008 CEBRA was going through a rough time. They didn’t have the funds to hire an architectural photographer. Instead, they bought a Nikon DSLR, and Mikkel started taking pictures for the office himself. He was known for the craftsmanship of photography long before 2008.

Kyrre: When did you start with photography?

Mikkel: My first camera was a fully automatic compact camera from Panasonic that I got for the confirmation. Haha! I mention this because I have always drawn, right from kindergarten. But taking pictures started at the age of 13 or 14. I already made an effort to take good pictures and spent time on them. I went a little further to take a good picture, or waited two [extra] minutes for it to be a good picture. My pictures were not fantastic, but I was already interested. At the School of Architecture, I bought a Nikon F3, which is one of the most used press photographer cameras, in brass houses. I was going to use it to take pictures of models and take pictures on study trips. I chose to keep it even after I bought a digital camera. It ended up being stolen in a burglary at home. Those who stole it must have thought they stole a digital camera, and were really disappointed when they saw what they got. But some of the very best pictures I have taken are with the analog camera. I know it’s a cliché, but when you have 24 or 36 pictures in a film roll, you make an effort with each picture. The pictures you take are the ones that are worth taking. The pictures I have from that camera are some of my best. Since I was familiar with Nikon, I chose to continue using the brand.

Kyrre: Tell me about your method for taking pictures.

Mikkel: In the beginning, I used the monkey method. The monkey method is based off an old saying that if you put a thousand monkeys and have them pound away on typewriters, they will in a hundred thousand years have managed to write Shakespeare’s collected works by pure chance. That’s the monkey method. It’s producing, producing, producing, and suddenly something amazing comes along. Using that method of course means that you should know when you strike gold.

In the past, I used to take a lot of pictures of each building. Let’s say I took 800 pictures. I would end up using 20. I have become better and better at not taking that many. It has something to do with the fact that I have become more skilled at exposing, become more skilled with manipulating raw images so I do not spend so much time on different exposures. I have more confidence to judge that my photo is correctly framed, so I do not have to take the same picture in ten different ways, and then sit at the PC and choose. I am slowly leaving the monkey method.

Typically I start at sunrise and end at sunset. I get morning light and I get evening light, and everything in between. I often return to the same motives. I draw with chalk where my tripod is or lay stones on the grass, and then I come back to the same place maybe five times during the day, but with different light. Short shadows, long shadows, reflection, stray light, direct light, and so on. I often end up having 10-15 positions that I know are good, and I visit them again and again as the sun moves. Therefore, I shoot from morning to evening. It is “worst” in the summer, where the sun rises at 04 and sets at 23, just like in Norway, or there it is perhaps even “worse.” In the winter you can do a building in eight hours!

Kyrre: What’s your view on including people in your pictures?

Mikkel: I think it is very important that there are people in pictures of architecture. It shows how the rooms are used, it gives a good scale, and a person can be a wonderfully important piece of the composition in a picture. Something I have always used, and which I later learned is a Sam Abell expression: Compose and wait. I often think; This picture would be great if some people came right there. Then I compose. Then I’m waiting. Waiting. Waiting. Pop! There it was. It could be a bike you are waiting for, or maybe a car. It is of course a staged reality, but often people, bicycles, cars become an important part of the composition you are looking for. Same with when taking evening photos. You might wait for a big truck with some good taillights. You know that too, the biggest part of taking pictures is really waiting, waiting, waiting. Then suddenly – click!, and the picture comes. But the whole evening was spent waiting. Waiting for the right light, waiting for someone to move, waiting for someone to come, waiting for an ugly car to no longer be parked there, waiting for a great Porsche. You name it. Wait. Wait. Wait. Not only wait for the right time of day, but also wait for the right time of year. Waiting for summer to come. Then the sun is high and hits exactly that facade. I can see that happening on July 13, and it is from then on that I can wait for a sunny day – or fog for that matter.

CEBRA has one go-to photographer; Adam Mørk. He has been taking pictures for them since the early 2000s. Nowadays they hire Adam for the most important projects. Otherwise, Mikkel will take time off his regular beat and go out with his tripod and camera.

Kyrre: Mikkel, does CEBRA ever hire any photographers besides Adam Mørk?

Mikkel: Oh no. In my eyes, he is the best — one of the best in the whole world! You do not have to work with anyone else when Adam exists. In addition to being an outstanding photographer, he is also an incredibly pleasant person. I actually graduated the same year as Adam. As students, we were in Finland together at a workshop in 1994. Even then, he was an incredibly nice person, extremely passionate about photography detail-oriented, and enormously knowledgeable about everything in photography. We were also interested in the same things like racing bikes and music. It just fits perfectly with Adam. He is so generous. He teaches me a lot about photography. So every time I get hold of him in one context or another, I ask about something, and he says you should do this and that, and you should buy this and that. He can sit and share for an hour about all his good tricks. It is enormously generous because he teaches me to take better pictures myself. He has a lot of commissions anyway, and he is driven by the fact that it is so exciting to talk to someone who is interested in the same thing.

Yesterday I looked at some of Adam’s previous pictures and he has actually developed quite a bit himself. It is interesting that someone who is so good can actually get better. It could be the equipment that has gotten better? I saw some pictures and thought “Okay, I could have taken that picture too.” I do not think that about the pictures he takes today. After all, he is the master.

Kyrre: What determines whether you hire Adam or take the pictures yourself?

Mikkel: It’s mostly practical. If there’s a small building in Risskov or Aarhus, it’s overkill to engage him. If it is the Experimentarium in Copenhagen, which is a large project, Adam is close by, and that makes sense. It also has to do with how busy I myself am. Basically, I don’t really have time for this, but sometimes you also have to do something fun!

Kyrre: You don’t just want to sit in meetings?

Mikkel: Exactly. That’s what’s cool about photography, it’s a good change. It’s another way to become a skilled architect, not just draw and draw and draw and be in meetings.

Kyrre: When you are done with a shoot, do you involve people at the office when you decide which pictures you will publish?

Mikkel: I do it myself. That’s what’s cool about working with images and working with visual art, as I do. You are yourself, and you make all the decisions yourself. You do not have to ask a builder, you should not have it validated by an engineer, you should not follow a building code, you have the peace to work alone with your own stuff, and I really like that. In hindsight, I see that I could have felt better as a human being as a visual artist and stood in a studio all alone all day. I’m really relatively introverted when it comes to the play, but I can talk to people like I do now, but basically I love being alone, working alone, making decisions alone. It’s just not possible to build large buildings alone, so then I’m forced into collaboration. But I feel best as a monk, and you can do that as a photographer!

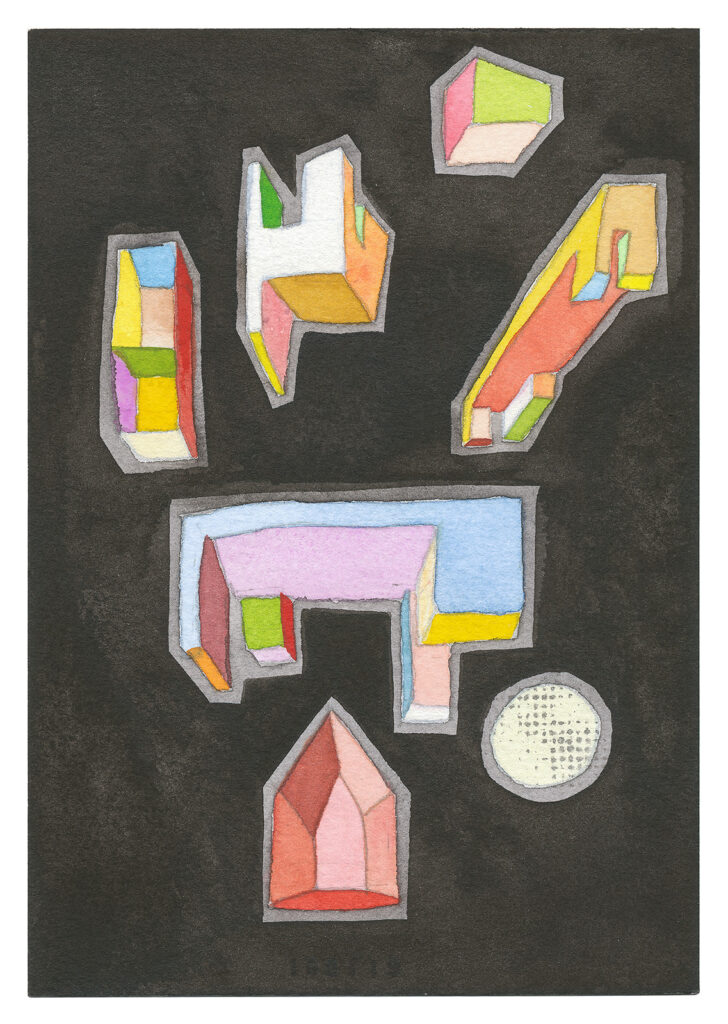

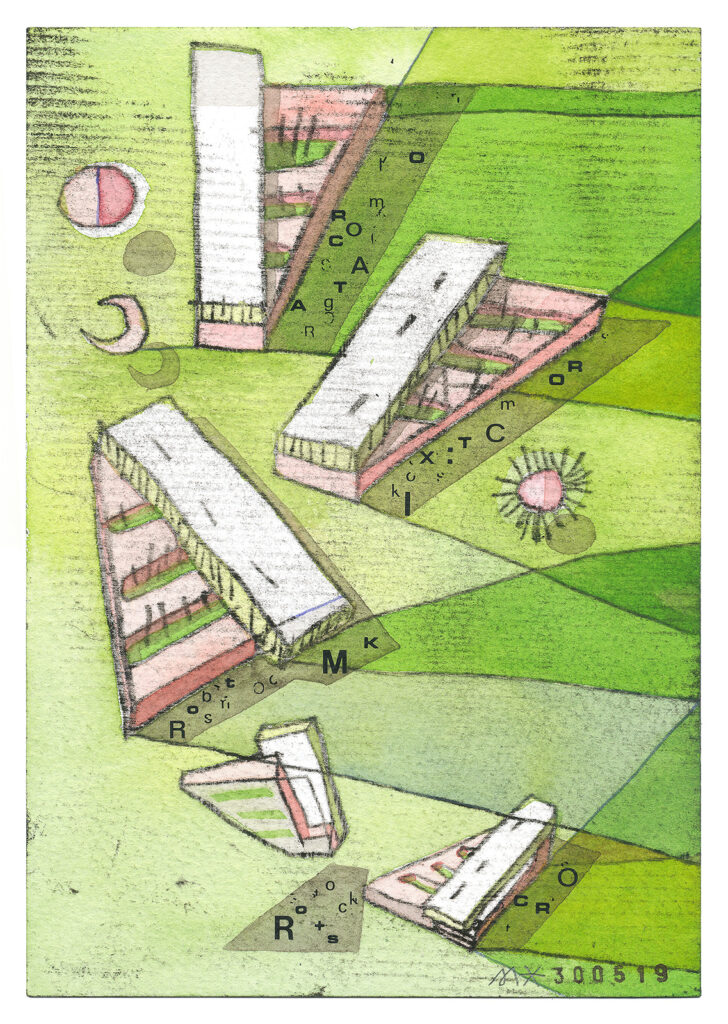

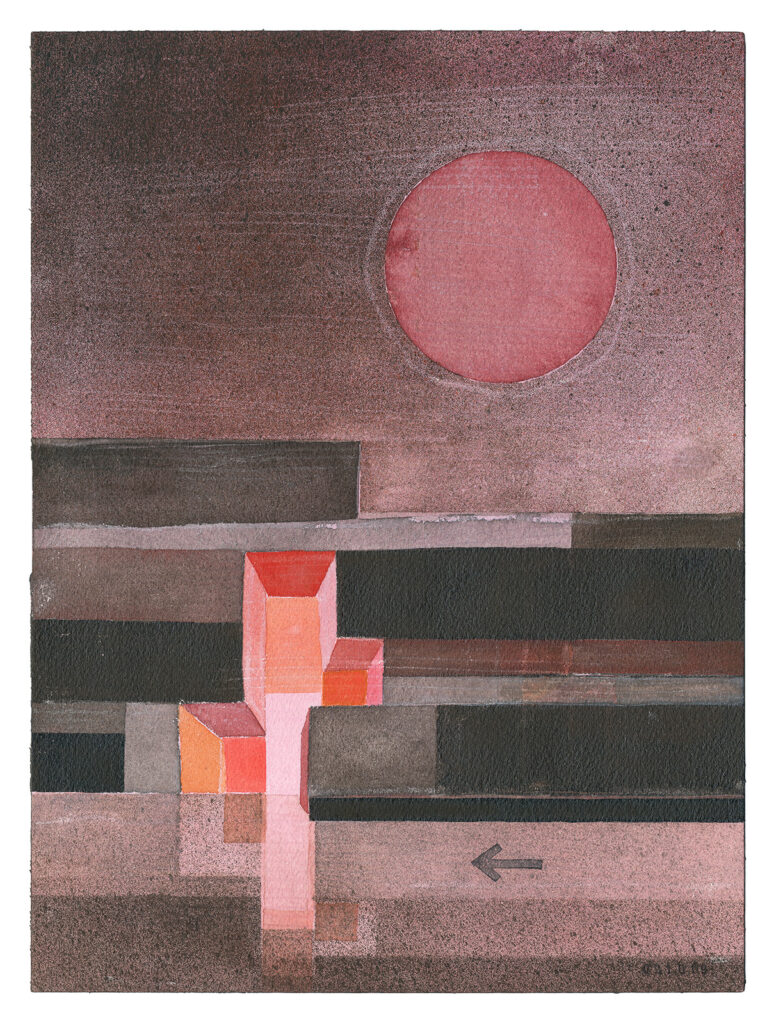

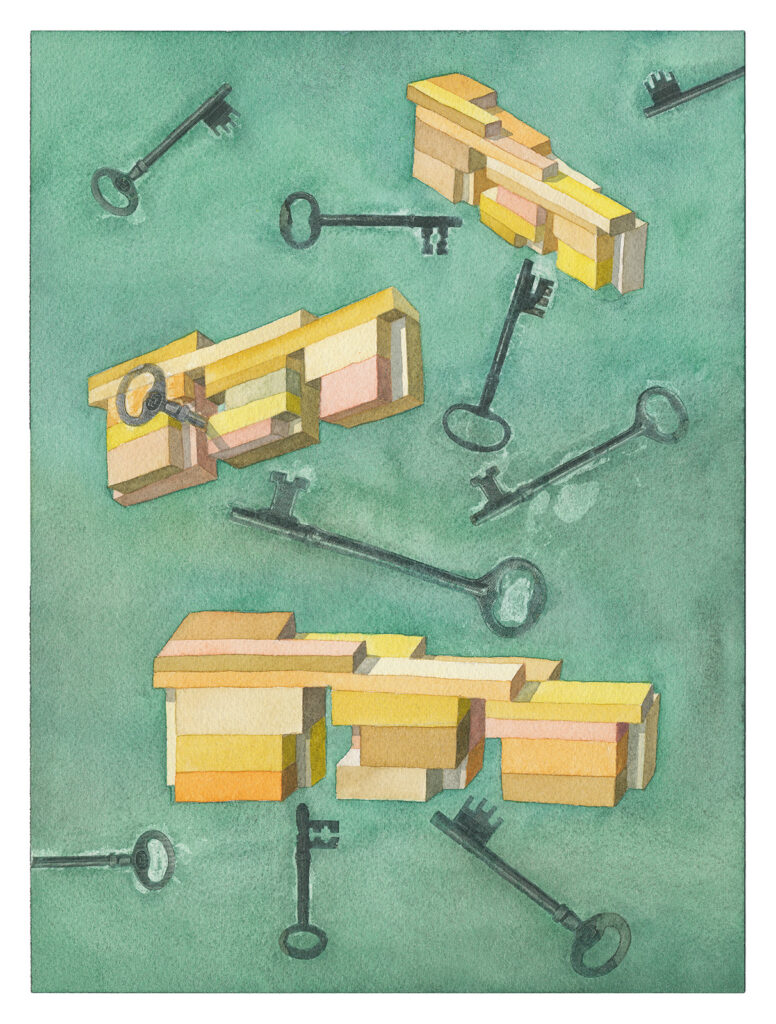

Kyrre: You feel a little like that already, maybe? With the sketches, watercolors, and woodcuts?

Mikkel: Precisely! It is a free space, one should not be part of any coalitions, one should not discuss with anyone, one should not speak for one’s cause, one should not sell anything. I only choose the colors I want, and I always know what is important – without input. It’s a great way to work. I am a little jealous of visual artists that way.

Photography for me is also free play and pure aesthetics. And I think that’s why I like to do it. There is free space. Not only a free space because you can work alone, but also a free space because you do not have to follow a space program. You’re pretty much free to do whatever the hell you want. This is what can be frustrating with the architecture, you are loaded on all sorts of obstructions, and limitations. I think we need eliminations, but not too many.

Kyrre: What is a picture worth to you? What do you get in return for the photos you take?

Mikkel: In addition to the fact that you can use the images to send to magazines and websites, to get more assignments and stand out on the architecture scene, there is also a form of evaluation of the work. How good is it? Where did it go wrong? What could we have done differently? Sometimes you think, shit, I’ve spent an insane amount of time on this detail, but it’s not really important. On the contrary, it may be that it is so good that one has fought for a decisive detail. It is as if when you look through a camera you see more attentively and in more detail. When you come home and zoom in and photoshop, you discover some things you had not seen while taking the picture. This means that you do a precise examination of a project. Like a doctor examining a patient. And you do not do that if you do not photograph the building. You can walk around and look at a project and say something about whether it is good or bad, but it is only when you take pictures for a whole day that you learn something about what you have done yourself.

What is also cool about being out taking pictures and standing there with your tripod; no one has any idea that you are the architect. And everyone wants to talk to a photographer. Who are you? Where are you from? Does this come in the newspaper? People also say what they think about what you stand and take pictures of. “I think it’s a strange thing.” You get good feedback on what people think about the project. I never tell who I am. I get to know everything! It’s really fun!

Kyrre: Beyond Adam, are there any other photographers you follow?

Mikkel: I look at a lot of pictures all the time, but I’m bad at noting what the photographer’s name is. That’s a little silly. But beyond Adam, I have mentioned Sam Abel. He has a bold philosophy. He is not an architectural photographer, instead, he has worked for National Geographic for two decades. I think his photography philosophy is fantastic. In reality, I have always done what he says to do, I just have not been able to put it into words, until he did it for me. He has helped me become aware of what I do. On the purely artistic terms of composition, I have always looked at Man Ray and Moholy-Nagy, sculptors from the Bauhaus school. This is because they always make the object or geometry have something to do with the frame. That the frame is never alone. That the frame has something to do with the image. That it hits a corner, that a diagonal or horizon lies in the middle or ⅓ point, or whatever. That the frame always flirts with the geometry that is inside the frame. That your frame, your square, is as important as the motif itself. You can learn a lot from the Bauhaus photographers. They play a graphic game, a subdivision of the surface.

Kyrre: How would you say your style has changed over time, or how your knowledge has changed how you take pictures?

Mikkel: I do not think I have changed stylistically, but I have become better at what I do. It is the same type of images and motifs I go for, but I’m better at exposing correctly, getting the images sharp, more careful with post-production. This is where I do not follow the Sam Abel doctrine. He thinks photoshop is dark magic. He does nothing with the pictures…not a single correction. He thinks it is morally wrong. He is pure. On the other hand, I am completely indifferent and manipulative. I do not mind replacing a sky with another sky during the day, or removing sockets, or inserting one more person in a picture. The image has nothing to do with reality. I’m not trying to document reality. I try to show architecture in the most beautiful way. I have to cheat. Move a chair out of the picture. That’s what I spend the most time on, moving furniture. At the villa in Risskov I had to take down a huge painting. I move a chair 5 cm, I move a table 2 cm and so on. I manipulate on site and when I get home I manipulate some more in Photoshop. I have become more skilled at the technical stuff. Stylistically, there is no change.

Kyrre: Thank you for taking time for this photo talk! See you soon!

Check out Mikkel’s Instagram where he shares sketches and watercolors.