Still Lives: Making Photographs During a Global Pandemic

When you’re obsessed with something, say, architectural photography, you can’t imagine a life without it, so you’re going to find a way to do it no matter what. Even in the midst of a pandemic, even if you have to use an awful camera, even if you just underwent back surgery.

In October 2019, I decided to take a break from work to address stubborn back pain that hadn’t gone away in about six years. Four months later, in late January 2020, I had surgery for it, which was scheduled to sideline me for three months. In March of 2020, the coronavirus pandemic halted the world. It had been six months since I last worked and I began feeling like I was losing my identity in the process, as architectural photography is what I’ve done for the last ten years.

Stuck inside and having participated in a number of podcasts, interviews, and Zoom calls, I became mildly fascinated with how friends and business acquaintances presented themselves online in these video chats. From cool studio spaces to bedrooms to grandparents’ living rooms, to the occasional that guy who uses the blurry Zoom filter so nobody can see what’s behind them, I was inspired to create a project where I’d be able to photograph people’s digital backgrounds.

After a few attempts and realizing the results just weren’t that interesting, the brain had an idea: What if I were to do architecture and interior photography using people’s webcams as my own camera? The logistics seemed daunting: I’d have to convince people to let me photograph their homes, then let me schedule them at a time of day with great light, and then get them to agree to me getting a full tour of their homes to find interesting angles, and go along with my half-baked ideas which would have them propping their laptop or phone up on a stack of books to get just the right composition. And then, god forbid, I’d get people to model for me, using their homes or favorite spaces as they normally would in front of a webcam (don’t go there, salacious reader). Most people are worried enough about their Nest thermostat doing this already, and now I’d be asking them to be willing participants.

It was just absurd enough, and if done right, the results could make for an interesting cross section of life during a global pandemic. I called a good friend of mine, Scott Hargis, who I often call to get feedback on my photos, client situations, proposals, etc to see what he thought of my idea. As soon as I pitched the idea, I was met with raucous laughter from the other side of the phone. Was my idea that terrible?!

Turns out Scott had been planning a similar project but had yet to begin. I’ll admit that I had a bit of an “oh, hell…forget it!” moment where I considered just throwing in the towel on the idea altogether. Quite disappointing, given how rarely I get truly good ideas for personal projects, but after about fifteen minutes of back and forth conversation, delicately hinting that the other one should just forget it (I kid), we agreed that we’d try to team up to make this a more varied and interesting project. Difficult, for both of us, as people who have built their lives around retaining creative independence.

Relying on our networks built over the years of traveling and photographing architecture, we began reaching out to those who at first would understand exactly what we were trying to do in order to build experience directing our participants with the camera. After a few strenuous and difficult attempts, we figured out the kinks (like having to give directions in reverse, signal strength affecting image quality, Apple for some reason only installing 720p cameras on their computers…), and came up with a system for making these things fun and interesting for those involved.

Our process would start with asking for a quick tour of people’s living spaces – with the laptop or phone held out at arms’ length. Thinking quickly, we’d look for interesting moments and make a mental note of where they were and how we’d like to photograph them. In some cases, photos presented themselves beautifully almost out of thin air.

“Stop! This is the shot! Right here. Set the laptop down and go hang out in that chair.” Even when you are shooting through a 720p potato-quality camera, a good photograph is a good photograph. Other times, we’d find an interesting angle and work through the camera and tinny speakers for 20 minutes having our helper style and arrange objects, adjust lighting conditions, or pose just right to create an interesting photo – in some cases, trying to get dogs and cats to model. It’s hard enough when you’re in the same room shooting with a real camera and lighting, but even harder when you’re halfway around the world doing it all in reverse. Somehow, everyone we worked with exercised incredible patience with us.

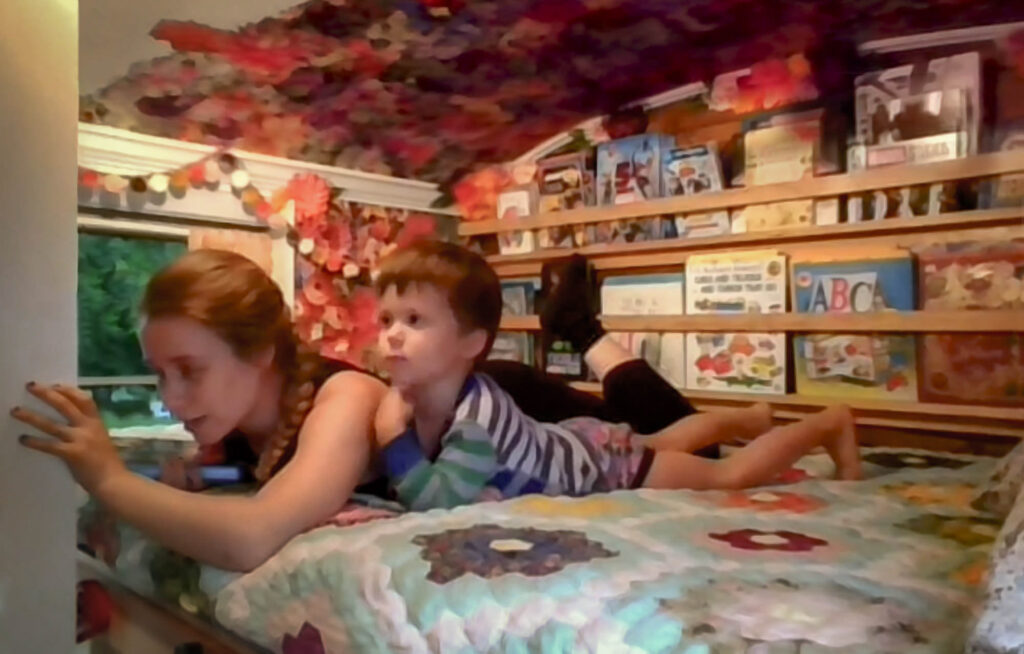

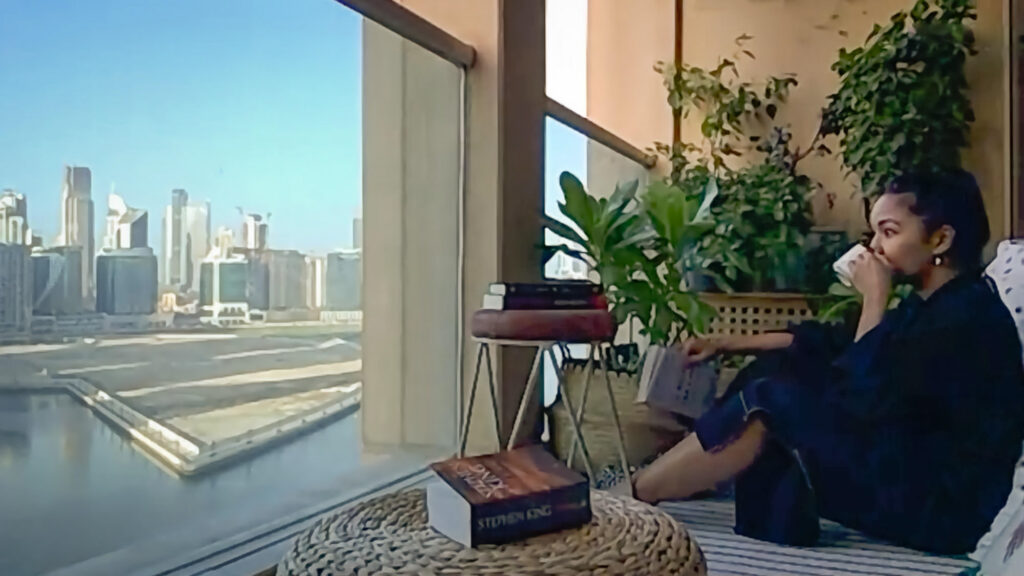

After ten or so digital “shoots”, we had our method down to a science and the project started to show a faint glimmer of progress. We were referred far and wide by our initial contacts, and were soon Zoom photographing people’s homes in places as far away as Nigeria, Greenland, Italy, New Zealand, and Dubai. The project began to snowball a bit, and I found the process oddly therapeutic. Seeing how friends were weathering the crisis was simultaneously humbling and inspiring. Making new friends in interesting places, even more so. From apartments in Nuuk, tents on the streets of Oakland, impeccably designed architectural homes, to high-rise apartments taken over by children, we experienced an incredible cross section of life around the world. We shared serious conversations about the state of the world and moments of laughter on nearly every call.

It also turns out that teaming up with Scott would be indispensably handy. Whenever one of us would question the merits of this project, the other one would be there to rally – and get psyched about the images we had created so far. After rejections (and there were a lot! Not everyone wants to let you into their home at the drop of a hat) it was nice to have a partner to vent to. And the objective views on images that we brought to each other when it came to critiquing and selecting finals was great, too; I can understand why some architectural photographers partner up full time. While I’m too stubborn to do it regularly, it was honestly a nice break from the usual solo operation.

On most calls, we ended up spending 20 minutes just chatting away like old friends, talking about life in a global pandemic, the kids being homeschooled, the virtues of online grocery delivery, or a shared passion for guitar, noticed only because I saw one in passing on our shoot. People seemed to genuinely enjoy showing us how they lived through lockdown – showing us their beautiful views, hobbies, animals, and just about everything else that fits in between four walls.

“Still Lives” is a photographic collaboration between two professional architectural photographers. Scott Hargis, based in Oakland, California, and Mike Kelley, based in Los Angeles, documented the architecture of “shelter in place” by using videoconference software to conduct remote photoshoots of people’s homes around the world.

The photographers conducted over 50 “virtual” shoots in more than 15 countries. The locations range from a low-income neighborhood of Lagos Nigeria, to a small village in Greenland, as well as cities such as New York, Sydney, Bordeaux, Auckland, and Phnom Penh. Luxury high-rise condos in Dubai appear alongside a tent on the streets of Oakland. Whimsical scenes and boisterous children compare with quiet moments of introspection.

During the live video calls, Kelley and Hargis directed their subjects to precisely place their laptop or phone to achieve a perfect composition. Then, working with the available light, they called for curtains to be opened or closed, and lights turned on and off, etc., until the exposure was optimal. When every element was complete, a screen shot was made to capture the image.

The COVID-19 pandemic forced billions of people around the world into varying degrees of social distancing, self-isolation, and quarantine. While the basic experience of “stay-at-home” living is easily translatable from one culture to another, the physical environments are unique to each individual. This photo essay seeks to explore the effect that one’s environment has on the otherwise unifying experience of self-isolation.

These intimate photographs carry the video graininess and digital blur we’ve come to associate with communication during social distancing, but they also contain an authentic record of life during the pandemic. The images are instantly relatable, even as the diversity of the physical environments becomes apparent.

Still Lives has been an incredible way to flex our creative muscles – and keep creating photographs even as our businesses have ground to a halt these last few months. It’s been especially interesting to remind myself of what makes a photograph good – and that the fundamentals are still important, no matter how bad the camera you’re working with is – these little webcams, with a pathetic dynamic range and horrendous lenses, are still able to produce something great when you’ve got a good story, good composition, and good light. These photos and the cameras they were made with are reminders of how we experienced, and continue to experience, so much of life during this pandemic, and we are thrilled to be able to share what we’ve created using them.

We can’t thank our participants enough for giving us their time to tour their homes and make photographs of and with them. We’re looking forward to continue to correspond with old friends using our new medium, and keeping up conversation with the new ones that we’ve meet throughout the process. To see the full series, which is constantly growing, you can visit Scott’s or Mike’s website.