Pictures That Move: An In-depth Look At Making Films About Architecture

“The two professions – filmmaking and architecture – are very close. Both require a plot: you have to develop episodes, a kind of montage that creates interest, and a sequence that gives the circulation, the path or the experience of building a certain suspense…”

Rem Koolhaas

Architecture and the moving image, and of course photography and the moving image, have a long, intertwined history. By the turn of the 19th Century, the technology that the early photography pioneers were still experimenting with had progressed to the point at which they could record a series of stills in an incredibly short amount of time, and play them back to animate the sequence. The built environment was the natural subject for the early photographers, with the long exposures required and architecture’s tendency to stay very still, and so by the time they were experimenting with the moving image, many of these early silent movies amounted to moving snapshots of the same scenes: people, horses, trolley cars moving through a cityscape.

By the time the 1930’s were underway, movies had developed narratives, multiple camera angles, storylines and sound. The world of architecture was quick to take notice with a flurry of films. Le Corbusier was an early adopter, working with Pierre Chanel on Trois Chantiers in 1931. From there Charles and Ray Eames played, Diller + Scofidio pioneered and MVRDV experimented.

We’re used to seeing great architecture used as a device in movies (all those wonderful Bond villain lairs), ads (Gehry in the early Apple ads) and music videos (Zumthor’s Therme Vals as the setting for a 1997 Janet Jackson video) but what can the moving image give to architecture?

My name is Jim Stephenson, I’m a UK based architectural photographer and filmmaker, and for this article I’ve spoken to other members of the community who are spearheading this new wave of architectural video; Sara Nunes in Portugal, Pedro Kok in Brazil and Jeff Durkin in the US. We spoke about three of the key differences between architectural photography and architectural film making…

Movement

The most obvious difference between photography and film making is movement. While a photograph can capture a single beautiful moment, in a film, people, light, vehicles, clouds, animals, the wind and rain all shift and move and suddenly we become aware of time passing.

“The films I do can add movement, sound, voices, the perspective of the architects, narratives, music, but all comes down to one word: time! Films add time!” Sara Nunes

There are two principle methods of movement in a film. The people and objects moving around, through, into and out of the frame and the camera moving across, around, over and through the subject. Like myself, and many architectural film makers, Pedro Kok came from a photography background:

“Since I adhere to the cannons of architectural photography, adding movement to motion picture was a tricky proposition. At the beginning, I thought movement should only come from the elements of a scene: architecture remained static, while people transformed the image though motion. Later, I added very slight moments as to highlight changes in perspective and the three-dimensionality of architectural space”.

While a static shot, with the camera remaining in one place as an observer of a scene, focuses the viewer and allows them to take in the detail, moving the camera can take us on a journey. As the foreground, mid and background slip over each other, a three dimensional space is created and the camera becomes the silent narrator of the film. There must be a reason to move the camera, with the key reason being to better tell the story of the building or architect “I use camera movement as a way to tell the audience where to look and what to feel about something” notes Jeff Durkin “It’s like the punctuation at the end of a sentence. Is this shot an exclamation point, comma or question mark?”

Sound

“If it’s done right you don’t even notice it, instead you feel it, it’s the emotional heartbeat of a film.” Jeff Durkin

Try watching a film on mute and see how different it feels. Even in scenes that contain no dialogue, so much of the feeling of a film is lost, and therefore so is the viewer’s attention. I often work with a sound designer, Simon James, and witnessing the work he puts into the ambient recordings of a space is remarkable. In the editing software you see layer upon layer of recordings, made with different microphones that each pick up something unique, combining to add a unique texture to the film. This texture is what creates an immersive environment for the viewer.

In addition to the atmosphere-creating ambient sound we can also add interviews and music to films. A spoken dialogue creates a narrative for the viewer and allows the architect, end-user, or anyone with a relevant voice to guide us through the key aspects of the building. The whole film can build from this element, as Jeff says, “The interviews are actually what I stress out most about getting right, and when I start editing the interview is the first layer I put together to give me a clear road-map of where the visuals go. Then I use music to layer in the emotion and punctuate certain feelings”. For Sara the music also tells a story about spaces; “I work with a sound designer, Ana Pedro Machado, every single week and every time that I can, I work with a composer, Bruno Ferreira. We even created a Soundcloud playlist with some of our favourite original music that we produce for our films”.

The Edit

Movement and sound are the most obvious differences between architectural photography and architectural filmmaking, but arguably the most important (and the one most frequently overlooked by people who are just starting out) is the editing process. Most photographers are familiar with making an edit of their images, (in this sense ‘the edit’ refers to picking which shots to give to a client and in what order, not post-processing), but the editing process in moving image adds an entirely new dimension and, in the early days of cinema, was the first thing that allowed movies to be considered an art form of their own.

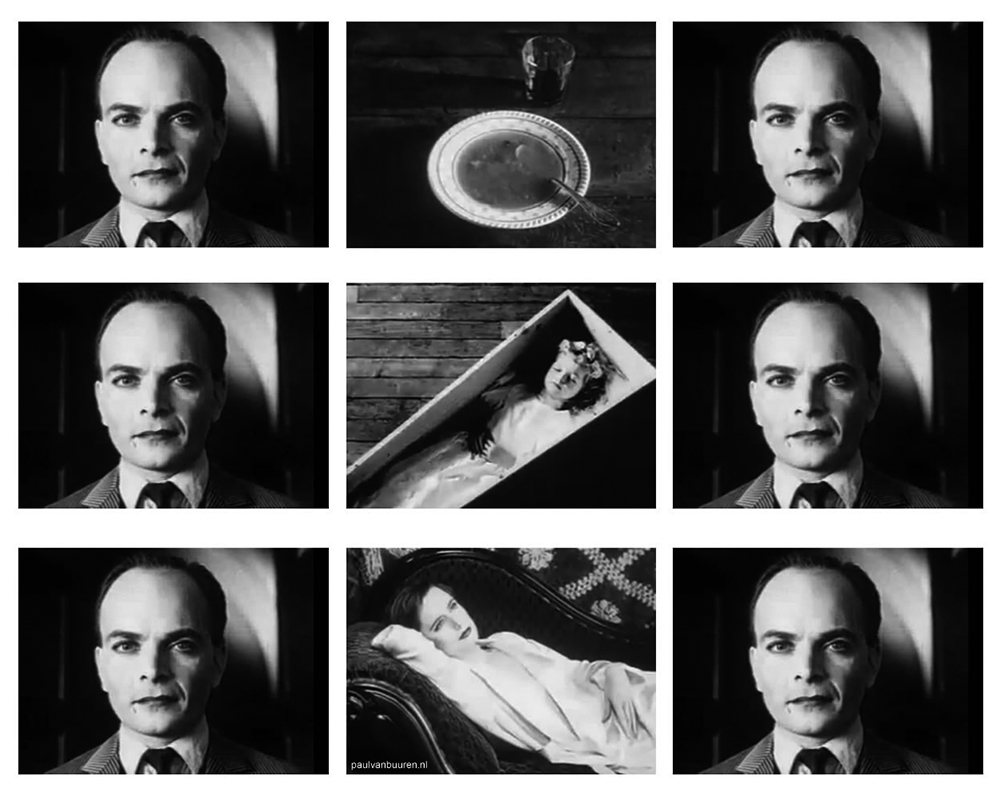

In the 1910’s and 1920’s, Soviet film maker Lev Kuleshov conducted a series of experiments. In his most famous one, he recorded matinee idol Ivan Mosjoukine looking at the camera with a neutral gaze. He then split this shot up and made three new films by inserting an image of a bowl of soup, then a girl in a coffin, then a woman reclining on a couch in the middle. Kuleshov noted how audiences marvelled at Mosjoukine’s incredible ability to depict hunger, grief and desire just with small expressions in his face. Of course, it’s the same recording of his face in each instance – the power of the edit is in the audience’s ability to form a story from a montage of shots.

“Editing for me is pure Architecture, and like Architecture I start with a set of plans by writing a script that outlines a beginning, middle and end” says Jeff “It gives me a framework to plug in who’s talking, what they are saying and how much time we dedicate to it. This gives me a clear story structure with the set-up, conflict, and resolution structured into a 3-5 min story.”

The edit is where everything comes together to form a real narrative. Every building has a story to tell, and while those of us who are also photographers continue to tell these stories through still images as well as moving ones, films allow us to take control of the story, as Pedro notes;

“From a documentary perspective, the films have allowed architects (and myself) to retain control of the narrative. Historically, architectural editors, publishers, curators and critics were the ones which built narratives around buildings. I like how project authors can add to this. Alternatively, when working with a narrative fiction, new and unexpected meaning can arise.”

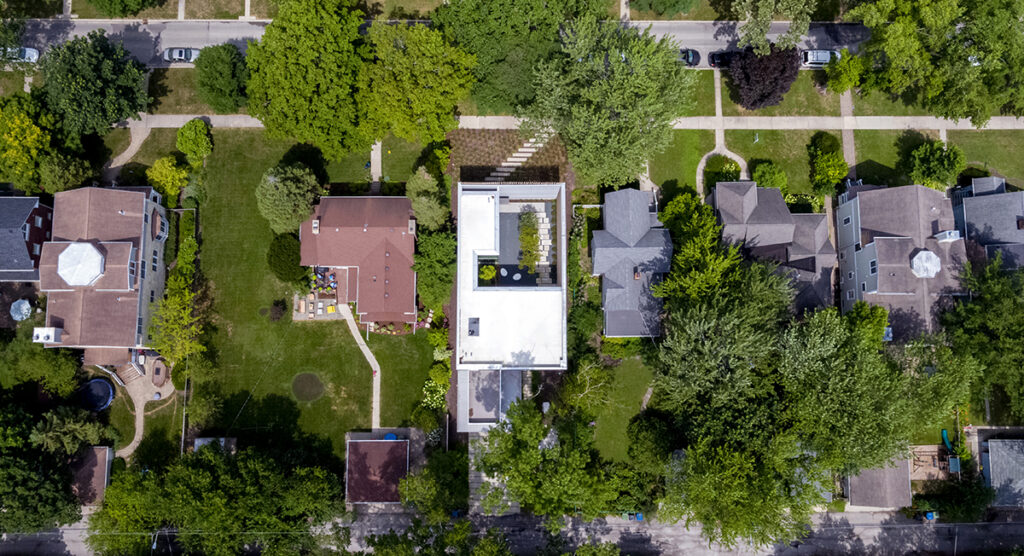

The story of the building can be didactic, with an architect clearly explaining the design intent over the top of shots that are full of visual information, or it can be looser and more experimental, verging on fictional. In “This was not my dream” by Pedro (above), Jeff’s film “Lipton House”, Sara’s “Mr Hulot” and my own film with the poet LionHeart (all below), we play with the idea of a different kind of storytelling.

However the story is told, the golden rule is ‘show; don’t tell’ – audiences like to have the chance to form these stories themselves, so it’s our job with the movement, sound and the edit to give them the tools to do so. To paraphrase Andrew Stanton and Bob Peterson (writers for some of the most compelling storylines in cinema through their work with Pixar), good storytelling never gives you 4, it gives you 2+2.

Sara firmly believes that “… architecture can change the world! We do it one film at a time, so for us is important that the films could be seen for the biggest number of people as possible.”

Now that we have the technology and the platforms to watch films smoothly and easily online and on social media, there’s never been a better time to be making movies. Right now, it feels like Vimeo, Instagram and YouTube are their natural home, but it’s worth looking out for the growing number of architecture and design film festivals that give us the chance to view some of the best films being made about buildings in cinemas and at outdoor screenings. The Architecture Player is also the largest repository of architecture films online and features work by Pedro, Sara, Jeff and myself.

Photography and film have so much in common. Both are excellent means of documenting a work of architecture, and both can be used to tell engaging stories; neither is more valuable than the other, but sometimes it might be worth considering adding a little movement, making some noise and bringing it all together for a beautiful narrative.

——————

Between us, Pedro, Sara, Jeff and I have made hundreds of films about architecture and the built environment. You can watch more here…

Jim Stephenson: www.clickclickjim.com / @clickclickjim

Sara Nunes: www.buildingpictures.pt / @building_pictures

Pedro Kok: www.pedrokok.com / @ kokpedro

Jeff Durkin: www.breadtruckfilms.com / @durkin.films