How One of the Biggest Names in Photography and Visualization Deals With Attribution and Licensing

DBOX is an international creative communications agency that creates campaigns in the sectors of luxury residential, hospitality, commercial, and cultural property. Specializing in both renders and photography, DBOX is at the top of the global architecture marketing game and were kind enough to sit down for a chat with APA to discuss their inner business workings, their frustrations, and their efforts to remedy an industry-wide scourge.

Matthew Bannister is the founder and principal of DBOX, and a specialist in architectural visualization (aka renderings) and photography. What started in the early 90s as a group of architecture students dabbling in computer graphics has by now evolved into a full-fledged studio. Instead of graduating and going off to work with architects, these students wanted the architects to be their clients. In 1996, DBOX was born and steadily grew into a full branding and creative agency; the core of the business is “visual making,” and they frequently combine digital rendering and photography to produce marketing packages that span conception to completion of some of the world’s most notable architectural projects.

DBOX’s creative process begins well before a foundation has even been poured. While it might seem somewhat premature, by creating visualizations and branding, they are able to add value to a product that isn’t built yet. As Bannister explains: “you can’t sell or lease something that doesn’t exist without visual storytelling.”

©DBOX Global

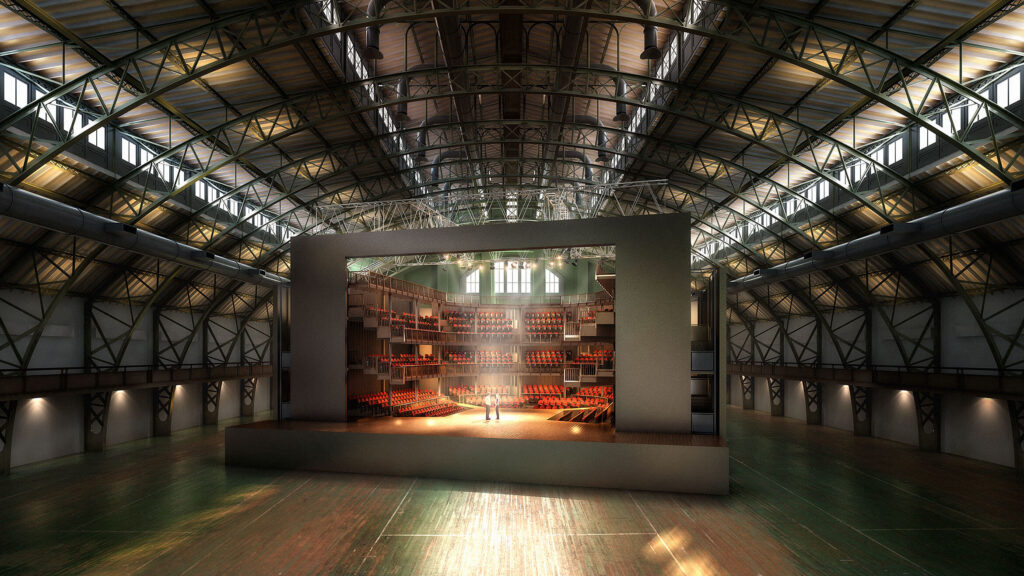

Like photography, the architectural visualization process is a collaborative operation between the artist and architect. It begins with sketches and model making, and the textures, lighting, and details are added in layer by layer, just like in photography. By working in both renders and photography, DBOX is not only able to serve the client before and after construction is finished, offering a seamless experience for the client, but they are also able to quickly work with their back catalog of photographs to add in backgrounds or details that are more difficult to create from thin air, like a city skyline, to their renders.

Over the years, DBOX has worked to refine their style into an unmistakable mix of photo-realism and dreamy ethereality. In decades past, the visualization of architecture was about showing a representation of the exterior of the building, or what a room looks like in its entirety – much like real estate photographers using an ultra wide lens to photograph the whole room. It has since morphed and grown: “Now we’ve reached a point where we said ‘well wait a second! We can show that there has been life here. We can leave a hat behind. We can leave a magazine that is open to a particular page on a table that gestures to the idea that somebody has just inhabited this space.'” This parallels modern architectural photography, in which many current practiotioners are working towards creating images with a bit more emotion and life in them. A decade ago, it was all about total perfection, but as renders have improved to the point that they can be indistinguishable from a photo, a little humanity goes a long way. DBOX was one of the first to start doing this 18-20 years ago, and more studios and artists are starting to catch on.

Take one of their most iconic works; a CGI photomontage of 432 Park Avenue where a ballerina poses in the window. It was made by compositing the 3D rendering of the space with the photo of the ballerina taken in a studio, plus the aerial images of Manhattan taken from a helicopter. It’s evident that these take an insane amount of work to make, especially when you consider that this building did not even exist when the photo was created! For those interested, here is a fascinating look at how these images were created.

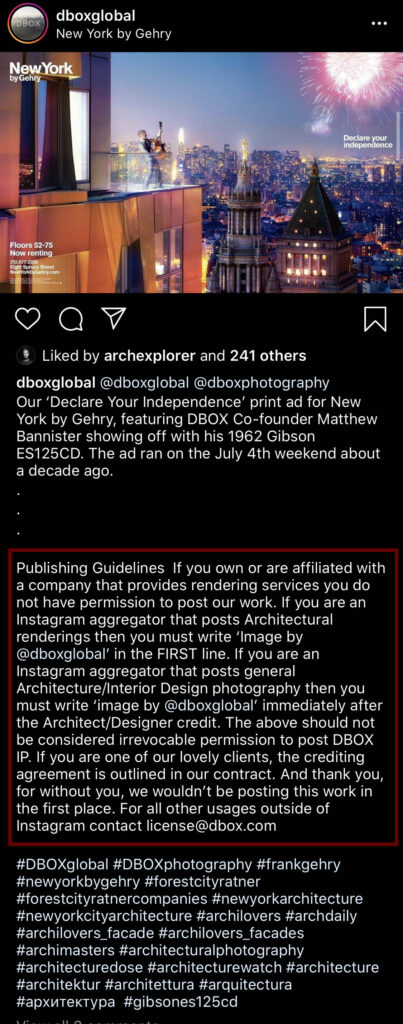

I’ll be honest: what caused me to reach out to DBOX was not solely their amazing work and history, which is without precedent. Everyone knows about it at this point. What caused me to reach out for this interview was their fierce protection of their intellectual property on social media, which looks like this:

In an era where photographers and artists are having their work stolen, misappropriated, miscredited, not credited at all, or profited off of with no compensation, DBOX has put their money where their mouth is and started to take a stand regarding the misuse of their images which take countless hours and an immeasurable amount of talent to create. Has this hardline stance affected their business? How do their clients respond? Has there been any backlash? Can the architectural photographer – us – take and adopt this strategy to protect our own work going forward? It seems like every day I’m getting hosed on social media – and I know you feel the same way too.

In DBOX’s Words

Mike Kelley: First of all, thanks so much for taking the time to sit down and chat with us today. To get started, what is DBOX’s social media strategy? Is it a source of work for you in that brands and developers are finding you on Instagram?

Matthew Bannister: Our developer clients know who we are and we end up on a shortlist of other agencies who do similar work to what we do. Our social media presence is directed more towards others who work in our industry of computer graphics and architecture. Of course, there are plenty of architectural industry suppliers and designers who follow us for inspiration as well. Our industry colleagues, including architecture hub accounts, publications, archiviz (rendering) studios — or you could call them our competitors — those are another component to our following. Archiviz is a pretty tight-knit community despite being competitors, just as it is, I’m sure you know, with architectural photography. While it can help to build our brand, we usually aren’t hired off the back of our instagram stream. Most of our work is referral based, and we’ve got a solid foundation of repeat clients as well.

Mike: Instagram is a bit of the wild west – where anyone can just take your photo and put it on their account which is monetized and they are in effect using your work for commercial gain. You get into this grey area where you are trying to differentiate who is using and profiting from your work. Is it a content aggregator? Is it a subcontractor of your client who had their work featured in your project? Are they making money off of that? Are they building a brand off of that?

Matthew: This is what is so outrageously unacceptable, and has made me blow a gasket before. I looked into it and realized there was A LOT of it going around. One day I was browsing through Instagram and came across an arch-viz aggregator account (for those that don’t know, an aggregator is an account that compiles imagery from a bunch of different sources). The account was posting other artists’ work under the guise of inspiration, but as I looked between the lines, it became clear that it was a rendering company that was posting everyone else’s work to gain followers and then peppered their work among the others to highlight it. All without permission.

I saw a pattern with many of the main architectural visualization aggregate accounts where they would post something, and then first comment or caption was always about following THEM or their hashtag, and then dot, dot, dot, and THEN they would hide the credit so low that you wouldn’t see it when you were thumbing through.

This pattern indicates that these accounts are burying the credit so that you’ll follow the account that posted the work as opposed to the person who made it.

So I polled my friends and colleagues in the industry asking if this practice was okay; I was met with a resounding “no”. “So after I made sure I wasn’t just being old and out of touch…I got some friends together and we went after as many of these Instagrams as we could, getting them to change their policies.

I think it’s better to get people to be part of the movement rather than to take them down, so I start with a polite email about crediting and copyright and the health of the industry. If they choose to be difficult, I’d CC other colleagues into the thread. If the offender still couldn’t be reasoned with then began the public shaming, and if THAT didn’t work, a takedown notice was issued.

Now all of the major reputable arch-viz aggregates are doing a first-line, ‘live tap’ credit.

Mike: The reason I became/have stayed so incensed is that I was talking to a friend of mine who runs an interior design Instagram page. He is an interior designer himself, and he often does sponsored posts. He has about 200,000 followers and was telling me what he gets paid to promote a sponsored post. It’s like $8k for a single permanent image, and $3k per story image which disappears after 24 hours. There are aggregators out there with over a million followers posting other people’s work. So they could at least take 5 minutes to credit the photographer, designer, the arch viz studio, whatever. There is a crazy amount of money at stake for these people, and they are producing no content of their own.

Matthew: A real company like Vanity Fair who accompanies visuals with text and stories and meaningful content can’t just rip off an image when they are going to print. They have a staff and reputation, etc, at stake. A 16 year old kid in a bedroom halfway around the world who has an eye for things that go well together doesn’t follow that code. And that’s why he can rip off your images and make six figures doing it. They are using an image to make money, but there is zero provenance or respect shown to the actual creator of the image or artwork. I hope that some day, Instagram will create some kind of guideline or framework within which intellectual property can be respected and a lineage can be traced to the creator that doesn’t require good faith on behalf of the account re-sharing the image.

DBOX’s Solution

Matthew was kind enough to walk me through DBOX’s credit requirements, which are very specific. Whether printed, for web, or on social media, lifetime credits are required within the first paragraph of the caption. The client’s project is usually the subject, so in most cases that is the first line of the caption; but the first comment needs a clickable credit, forever. No matter what the medium is, the credit policy is the same.

Matthew thinks that we struggle with credit and copyright because digital work, whether that be visualization or photography, has been cheapened. Digital sharing and the internet’s accessibility is a double edged sword which has both created opportunity yet at the same time has eroded the clout of photographers and artists alike. A further damper is put on it by people that are willing to work for free or without a contract.

Matthew Bannister, DBOX

“If the critical mass aren’t acting professionally, then professional photography slowly, piece by piece, disappears. Without people acting like professionals, before long, you won’t have a profession”

It is imperative then, that photographers and visualization artists act professionally. Take the time to protect yourself and your work with solid contracts and clarity regarding intellectual property, licensing, and credit. Matthew clarifies that “if you retain the copyright for your work, you can decide wherever it goes. If somebody posts it and you don’t like that, you can take it down. If you don’t retain the copyright, you can’t; you lose control.” Take that as yet another reminder to register your work with the US Copyright Office or your country’s analogous organization.

There has also been some criticism of DBOX’s stringent guidelines; some think that Matthew’s “Credit Revolution” policies are too far-reaching in an era where reposting is so commonplace and almost expected by architect and design clients. To that, Bannister, who has worked for decades to establish a brand which his clients can trust to deliver what they need; says: “these are our policies and if you don’t like it, you don’t have to hire us! If the younger group [of photographers and artists] begins to accept this behavior as normal, then it’s game over for the entire industry.”

While this stance may seem alarmist, there is truth to it. We have already seen the effects of photographers giving away their rights to credit and licensing; one need look no further than the real estate photography industry as evidence of the reduced fees and complete and total lack of credit given to photographers on almost every post. Will this one day come for the commercial and editorial side of the business? Without some degree of enforcement, it’s highly likely.

A sample contract

Worried about your images being pilfered and spread across social without credit or permission? Here is some sample contract language developed in cooperation with The Credit Revolution and DBOX that you can use to protect yourself.

- X is the sole and exclusive author and owner of any and all work product conceived and/or created in the performance of the Services hereunder and any work product conceived of, created and/or developed by X prior to, independent of or outside the scope of this Agreement (the “X Works”), but not of any works in the public domain, works owned by a third party, or works owned or controlled and provided to X by Client. Logos and tradenames created for and finally approved by Client shall be deemed the exclusive property of Client. X shall have the sole right to file copyright registrations and the applications therefor with respect to the X Works with the U.S. Copyright Office but shall have no obligation to do so. Under no circumstances shall any of the X Works be deemed to be a “work made for hire”.

- X hereby grants to Client and Client’s agents a nonexclusive, nontransferable, royalty-free license to use, reproduce, distribute and publicly perform and display the X Works solely to promote the Client’s business, and for public relations, planning, marketing and the advertising of the project. Client agents shall be bound by the same restrictions relating to the X Works that are applicable to the Client, including but not limited to the requirement for giving credit as set forth in Section 8 below. Except as explicitly set forth herein, Client may not modify, reproduce, decompile, reverse engineer or modify any of the X Works without X permission. Except as explicitly set forth herein, the license granted in this Section specifically and without limitation does not include the right to license, sublicense or otherwise allow any use of any of the rights granted in this Section to or by any third party, including but not limited to Client’s affiliates, agents, third party vendors, contractors, real estate brokerages, real estate brokers, subcontractors, architects, designers, interior designers, engineers and/or construction companies. The license granted in this Section for each particular X Work is expressly conditioned on the completion of that particular X Work by X and full payment for that particular X Work to X from Client and no license shall be deemed granted for a particular X Work unless and until such conditions precedent are satisfied in full.

- In order to evidence that X is the owner of the copyright with respect to all X Works and to give the proper professional credit to X, the Client shall cause the following notice to appear visibly near or at the bottom of each reproduction of each X Work whenever it is used: “© X” or “© X for Clientname”.

In the event that content produced by X (rendering, photography, video, etc.) is posted to Instagram by or on behalf of the client, the text caption must include “@X” and the hashtag #X” The credit should read “Image by @X”. It can also read “imagery by @X for clientname”. These attributions should be included in the initial post’s caption, not in a subsequent comment.

In the event that content produced by X (rendering, photography, video, etc.) is posted to Facebook by or on behalf of the client, the text caption must include a direct link to X’s Facebook page (entering “@X” will create a live link) and the hashtag #X” The credit should read “Imagery by @X”. These attributions should be included in the initial post, photo, or video’s caption, not in a subsequent comment.

In the event that content produced by X (rendering, photography, etc.) is posted to Twitter by or on behalf of the client, the text caption must include X’s Twitter handle “@Xl” and the hashtag #X” This credit should read “Imagery by @X”

YOUTUBE

In the event that content produced by X (photography, video, etc.) is posted to YouTube by or on behalf of the client, the text caption must include a direct link to X’s website (www.X.com) and the hashtag #Artistname.” The credit should read “Imagery by www.X.com”

All other Social platforms known or unknown should conform to the above guidelines as much as reasonably possible.

Bottom Line

It’s clear that both the visualization and architecture photography community need to draw a line with regards to credit, usage, and licensing. While more traditional clients such as architects and interior designers have been understanding and responsive to the requests for credit, other entities perhaps have not been so open to the idea, which needs to be an industry-wide standard. As the need for our services expands on a near-daily basis thanks to the internet-based exposure required of new development projects, clients, their clients, and aggregators/hubs must be educated on proper usage and credit.

What do you think of DBOX’s stance? Have you been frustrated by content theft and reposting by accounts with less than good intentions?